Pandemic-Era Trends in Estate Tax Collections

The code used to generate the calculations in this post can be found here .

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) temporarily cut estate and gift taxes by increasing the exemption—the amount of wealth below which no tax is owed at death—from $5.5 million to more than $11 million. This change, which took effect in 2018 and is scheduled to expire at the end of 2025, was projected to reduce estate tax revenues by about one-third according to official scorekeepers at the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT).

During the first two years of this new regime, receipts fell as expected: in fiscal years (FY) 2019 and 2020 (which mostly reflect deaths in 2018 and 2019), collections averaged about $17 billion annually, down from an average of $23 billion in the two years prior and lower than the $25 billion projected under CBO’s pre-TCJA baseline.1

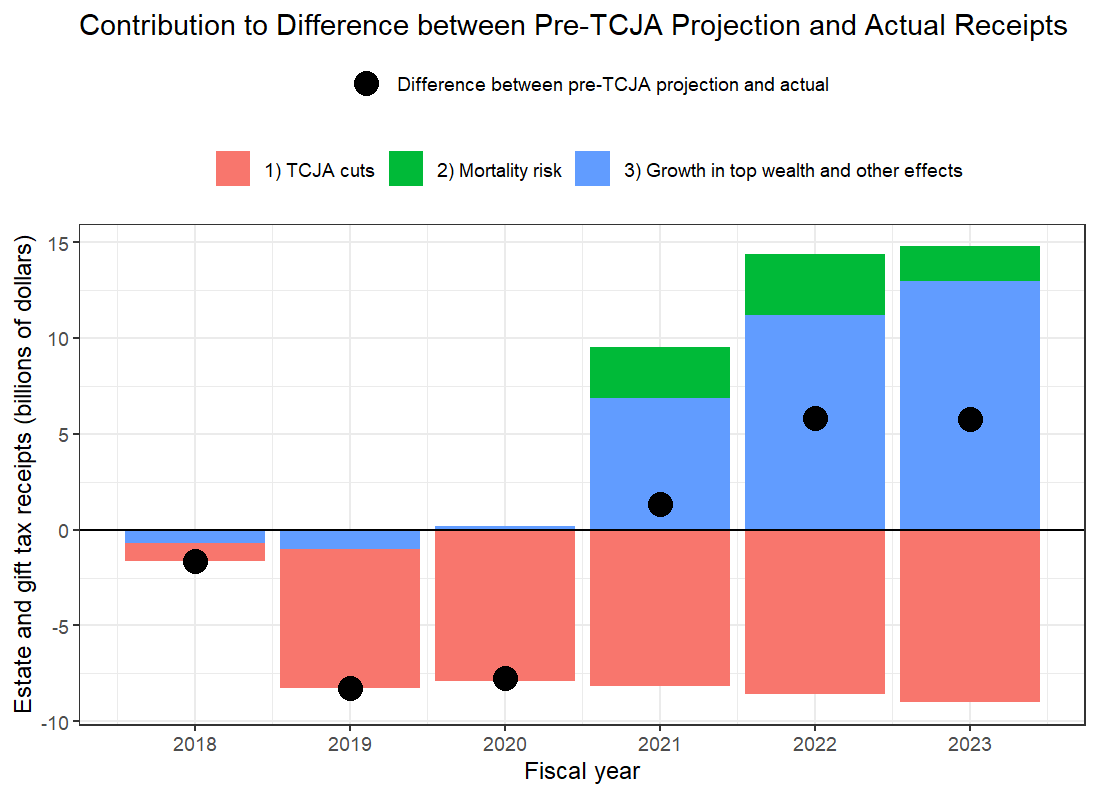

But beginning in FY2021, the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic began to show up in estate tax collections. Both household wealth and mortality risk, the two major determinants of the estate tax base, rose markedly during the pandemic. Since FY2021, estate tax receipts have exceeded not only post-TCJA projections—they have exceeded pre-TCJA projections. In other words, the combination of excess mortality, excess saving, and higher asset prices have more than offset TCJA’s estate tax cuts. We ballpark the relative importance of these factors through FY2023, visualized below. (These calculations are based on a toy model and should not be understood as an official Budget Lab score.)

“Pre-TCJA projection” is the estate and gift tax projection from CBO’s June 2018 Outlook plus the legislative component of baseline changes from the April 2018 Outlook.

Excess mortality explains at most one-quarter of the non-TCJA component of the discrepancy between projected and actual receipts—probably less, given Covid-19 risk disparities. Even after accounting for excess mortality, actual receipts still exceeded expected receipts by more than 50 percent in FY2022 and by more than 60 percent in FY2023. We believe that most of this discrepancy is due to higher-than-expected growth in household wealth, which grew by 48 percent for the top 0.1 percent during the pandemic. Some of this growth took the form of capital gains: from TCJA’s passage through 2022, the S&P 500 rose 46 percent (reaching a peak of 75 percent in 2021), home prices grew by 50 percent.2 The rest of this unexpected growth in net worth was excess savings, much of which ended up on the balance sheets of richer households.

With tax filing season now complete for FY2024, we can see that estate tax collections remain strong but are down from last year’s historic peak. This decline likely reflects the end of the acute phase of the pandemic, lower stock prices for much of FY2023, and the roll-off of a mysterious record-setting tax payment last year.

One subtle implication of these record-breaking revenues is that TCJA’s estate tax cuts have been more costly than anticipated. As shown above, due to unpredictable pandemic-related effects, the estate tax base has been much larger than was expected at the time of TCJA’s passage. This means that more wealth was transferred tax-free during the pandemic than would otherwise be the case if pre-TCJA law were still in place.

We can estimate this forgone revenue with a back-of-the-envelope calculation. If (a) JCT’s initial revenue estimate was correct conditional on economic assumptions and (b) increases in mortality risk and asset prices were uniform with respect to the distribution of wealth, then absent TCJA’s changes, annual estate and gift tax receipts would have approached $40 billion to $50 billion annually over the last few years—about $15 billion more per year than actually collected.

Footnotes

- Estates are generally required to file estate tax returns no later than 9 months after the decedent's death, meaning that most receipts in a given year reflect liability incurred from deaths in the prior year.

- While we don’t know CBO’s exact pre-TCJA projection in taxable estate, estate and gift tax revenues were projected to grow by about 13 percent and nonworking adults (a rough proxy for older population) was projected to grow by about 7 percent from 2018 through 2023. The observed growth in asset prices would then imply that actual estate revenues should be 1.5 / (1 + (0.13 - 0.07)) - 1 = 41% higher than expected, which means asset prices explain between two-thirds and 80 percent of this remaining discrepancy.