The TCJA’s Tax Benefits for Parents Are Shrinking

Key Takeaways

-

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) consolidated child benefits in the tax code by eliminating dependent exemptions but increasing the Child Tax Credit (CTC), leading to tax cuts for most parents.

-

While dependent exemptions were indexed for inflation, the CTC is not. This means that extending the TCJA in 2026 would deliver smaller average tax cuts for parents than it did when first enacted in 2018.

(Note: the code used to produce the calculations in this report can be found here.)

Most individual tax provisions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) are scheduled to sunset at the end of this year. As the debate over extension heats up, it’s important for policymakers to consider how TCJA’s effects in 2026 would differ from its effects when first enacted in 2018.

One example is how parents are impacted. In 2018, the TCJA’s consolidation and expansion of child-related tax benefits led to meaningful tax cuts for many parents. But because dependent exemptions, which are indexed to inflation, were replaced with a more generous Child Tax Credit (CTC), which is not indexed to inflation, TCJA’s benefits for parents have been falling over time.

In this post, we look at the distributional impact of the TCJA’s child-related tax provisions—both the actual effects from 2018 and the projected effects of a potential extension in 2026. We find that the TCJA’s exemptions-for-CTC trade would deliver smaller average tax cuts in 2026 than it did for parents than in 2018, with uneven effects across the income distribution.

How the TCJA Reformed Child Tax Benefits in 2018

The TCJA was designed to both simplify and cut individual income taxes. It did so by eliminating certain deductions, consolidating like-minded provisions, and reducing tax rates. For most taxpayers, tax cuts outweighed the loss of certain tax benefits elsewhere: an estimated 80 percent of taxpayers saw tax reductions in 2018.

One example of tax benefit consolidation in the TCJA is the tax treatment of children. Prior to the TCJA, the tax code offered both a deduction (dependent exemptions) and a credit (CTC) for most children. The TCJA consolidated these tax preferences by first repealing dependent exemptions, then expanding the CTC—both in terms of maximum value (which rose from $1,000 to $2,000) and overall reach (the income limit for married parents rose from $110,000 to $400,000). In other words, the TCJA traded dependent exemptions for a more generous CTC.

For parents, the value of this exemptions-for-CTC trade depends mostly on income. On one side of the ledger is the loss of dependent exemptions, which were scheduled to be $4,150 per child in 2018. Like all deductions from taxable income, exemptions only generate tax savings if a taxpayer has positive taxable income to offset, and because the income tax system is progressive, the tax savings from deducting $4,150 grow with income.1

Credits, on the other hand, reduce tax liability dollar-for-dollar. Some credits are refundable, meaning that they can be claimed even if credit value exceeds liability—a common situation for lower-income families who owe little or no income tax. The CTC, under both its pre-TCJA and TCJA designs, is partially refundable. For parents who don’t earn enough to owe much in taxes, a portion of the credit is available as a refund based on income earned from working. The practical effect of this phase-in design is that while most bottom-quintile families benefited somewhat from the TCJA’s CTC expansion, that benefit was less than the full $1,000 per child tax cut available to middle- and upper-middle-income families. This is especially true for low-income families with multiple children.2

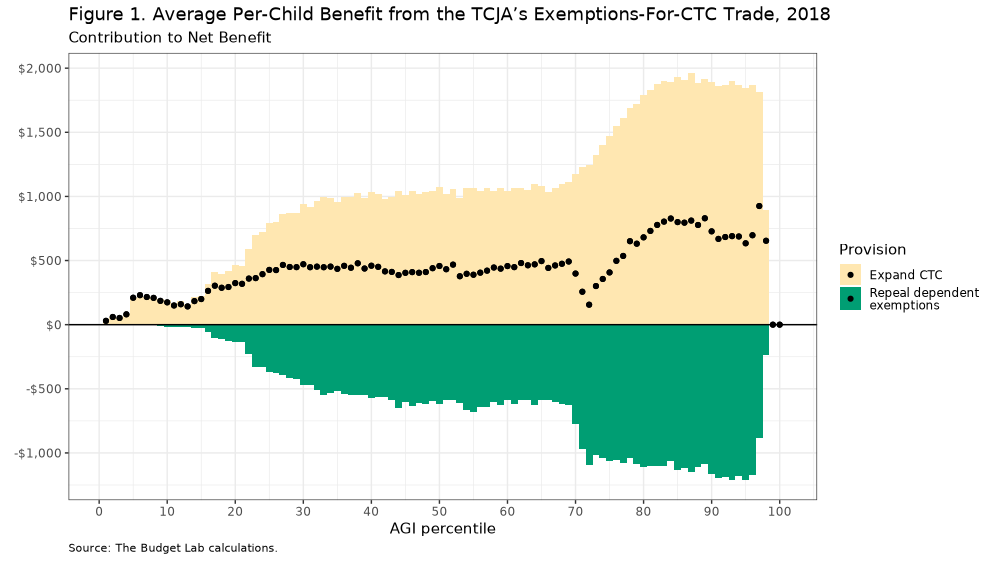

How these design features interact with the real-life distribution of parents’ income is an empirical question—one that we can answer with our tax microsimulation model. We estimate that 91 percent of parents in 2018 were made better off by the exemptions-for-CTC trade, and that the average tax savings was about $400 per child.3 Figure 1 below decomposes the net impact by provision across income groups, underscoring several distributional takeaways:

- For low-income parents, the net benefit was smallest. Exemptions did nothing for those with no taxable income to begin with, but the CTC’s phase-in provision—sometimes referred to as a “work requirement”—means that only a fraction of the larger credit was made available to them.

- Middle-income families lost about $500 per child in exemptions but gained the full $1,000 CTC increase.

- Upper-middle- to high-income parents saw larger dollar-amount net benefits. This is because these taxpayers were phased out of the pre-TCJA CTC design, so their increase in CTC under the TCJA was more that $1,000 per child. But this group faces higher marginal tax rates and felt the loss of exemptions most intensely.

- For those at the very top, the trade was worth $0. both CTC and exemptions phased out entirely when income exceeded an income threshold.4

AGI percentiles are calculated with respect to tax units with children and positive income and are weighted by number of parents.

While the absolute value of the TCJA’s child benefits trade rose with income, it was generally larger as a share of income for lower-income groups. That is, by converting the deduction component into a flat-dollar benefit, the TCJA made child tax benefits more progressive—with the caveat that, due to the CTC’s earnings phase-in, benefits for the lowest-income families remain limited.

How Inflation Changes the Math for 2026

Like most provisions in the tax code, dependent exemptions are automatically adjusted for inflation each year. We project that the per-child exemption value will be $5,300 in 2026 after the TCJA expires—up from $4,150 in 2018. The CTC, however, is a rare example of an unindexed tax provision. Its $2,000 maximum value (and its associated eligibility income cutoffs) have remained unchanged since 2018. The bout of unexpectedly high pandemic-era inflation means that the CTC’s real value has been eroded in recent years. If it had been indexed to inflation, the CTC’s value would be $2,500 in 2026, not $2,000.

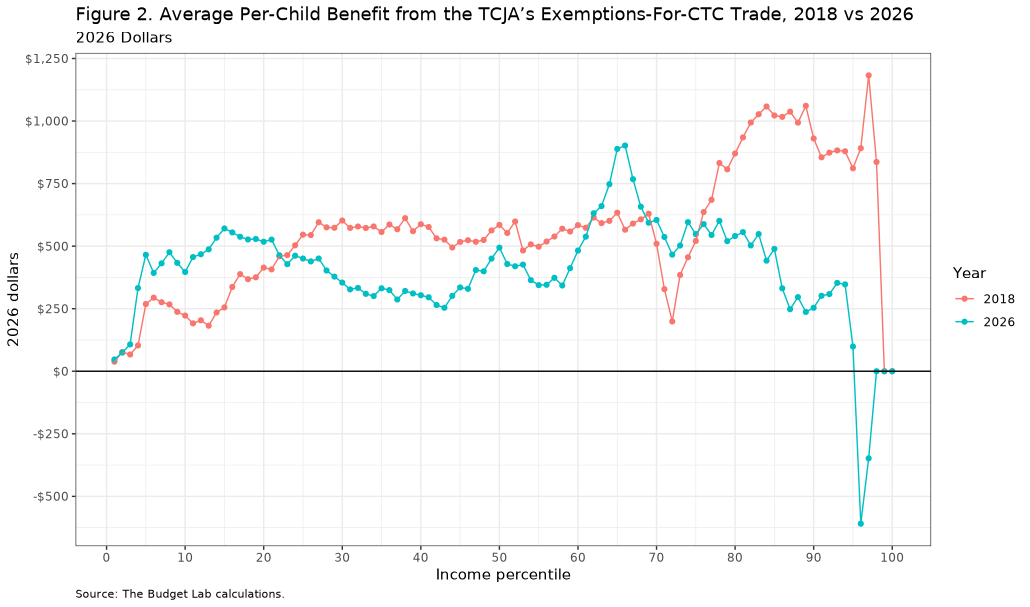

In other words, inflation has caused the positive side of the exemptions-for-CTC ledger to shrink over time. If the TCJA were simply extended in 2026, its child-related tax provisions would have a different distributional impact on parents than it did in 2018. Compared to 2018, slightly fewer parents in 2026 would benefit from TCJA’s overhaul of child-related provisions (falling from 91 to 87 percent). But the per-child average benefit, expressed in 2026 dollars, would fall from $520 in 2018 to $400 in 2026—a decline of one-quarter.

Breaking these numbers down by income, visualized in Figure 2 below, reveals a more nuanced picture.

Benefits have shrunk for most parts of the income distribution. For families ranking in the middle and top parts of the income distribution, the unindexed CTC has been eroded by inflation while the forgone value of dependent exemptions grows with inflation.

But the TCJA is better for some in 2026. Because the unindexed CTC phases in with earnings, and wage growth has been strong among lower-income workers in recent years, low-income families are now able to claim a greater share of the CTC than they were in 2018.5 Similarly, parents ranked in the fourth quintile are now earning enough to be fully phased out of the pre-TCJA CTC design, which was not the case in 2018. That means the TCJA would offer them a CTC increase of $2,000 in 2026, larger than the $1,000 from 2018.

AGI percentiles are calculated with respect to tax units with children and positive income and are weighted by number of parents.

Conclusion

Our simulations show that extending the TCJA’s child-related changes would have more muted benefits for parents than it did when first enacted in 2018, on average. But that difference between effects in 2018 and 2026 varies with income—and is even positive for some points in the income distribution. This underscores an important point about tax policy design: if left unindexed to inflation, the real burden of taxes will shift over time, often in subtle or unintuitive ways.

Footnotes

- For example, for a taxpayer facing a 10% marginal tax rate, a $4,150 deduction saves them $4,150 x 10% = $415 in tax liability. For someone in the 32% tax bracket, the deduction is worth $4,150 x 32% = $1,328 in tax savings.

- Our analysis of CTC reform options discusses the distributional and microeconomic implications of these design choices in further detail.

- We estimate the effects of these provisions against a baseline that includes all other individual provisions of TCJA. For example, the value of personal exemptions is computed in the context of TCJA’s lower rates.

- The TCJA CTC phases out at a rate of 5 cents per dollar of AGI above $400,000 ($200,000 for non-joint returns). In 2018, under pre-TCJA law, personal exemptions would have phased out at a rate of 2 percent per $2,500 of AGI exceeding $266,150 (single) / $319,400 (joint) / $159,700 (Head of Household).

- This dynamic can be thought of as “bracket creep” when marginal tax rates are negative.