Who Benefits Under Each CTC Reform?

Key Takeaways

-

Because each CTC reform option provides a flat-dollar benefit increase, benefits are generally largest as a share of income for lower-income groups.

-

The lowest-income families, who do not qualify for the full credit value under current law, require an elimination of the phase-in to see full benefits.

-

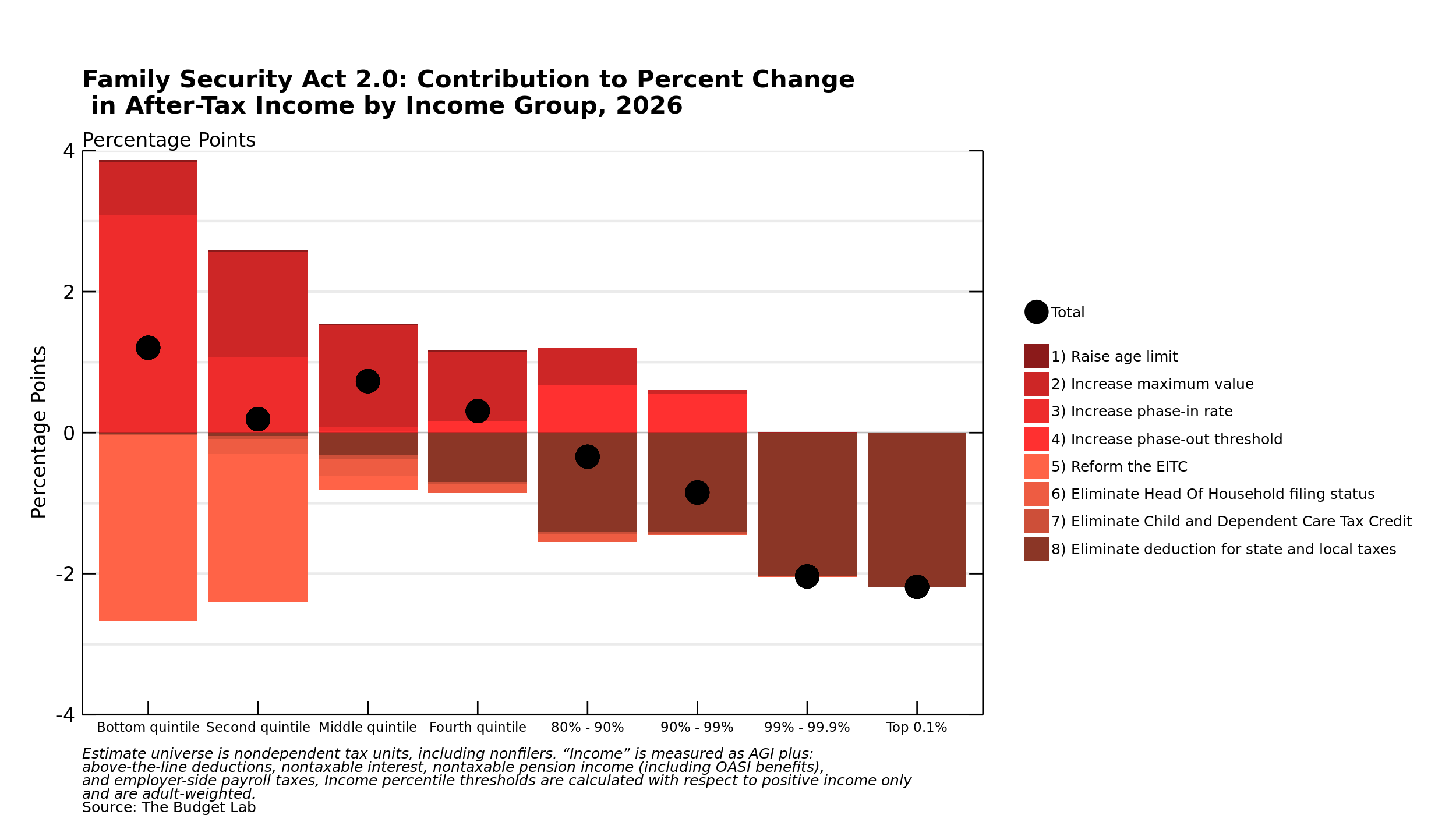

The full FSA reform option consolidates child-related benefits in the tax code, some of which are targeted to low-income parents. On net, the bottom four quintiles would benefit, though some parents would be made worse off. High-income families would see tax increases due to SALT deduction repeal.

This page highlights several notable findings about the distribution of fiscal impacts by income. Please see this companion piece for more information on how we calculate distributional metrics.

The figure below illustrates how each scenario affects after-tax income by income group.

- The figure above highlights the general structure of the CTC: given a flat credit value and a phase-out, benefits are generally largest as a share of income for lower-income groups.

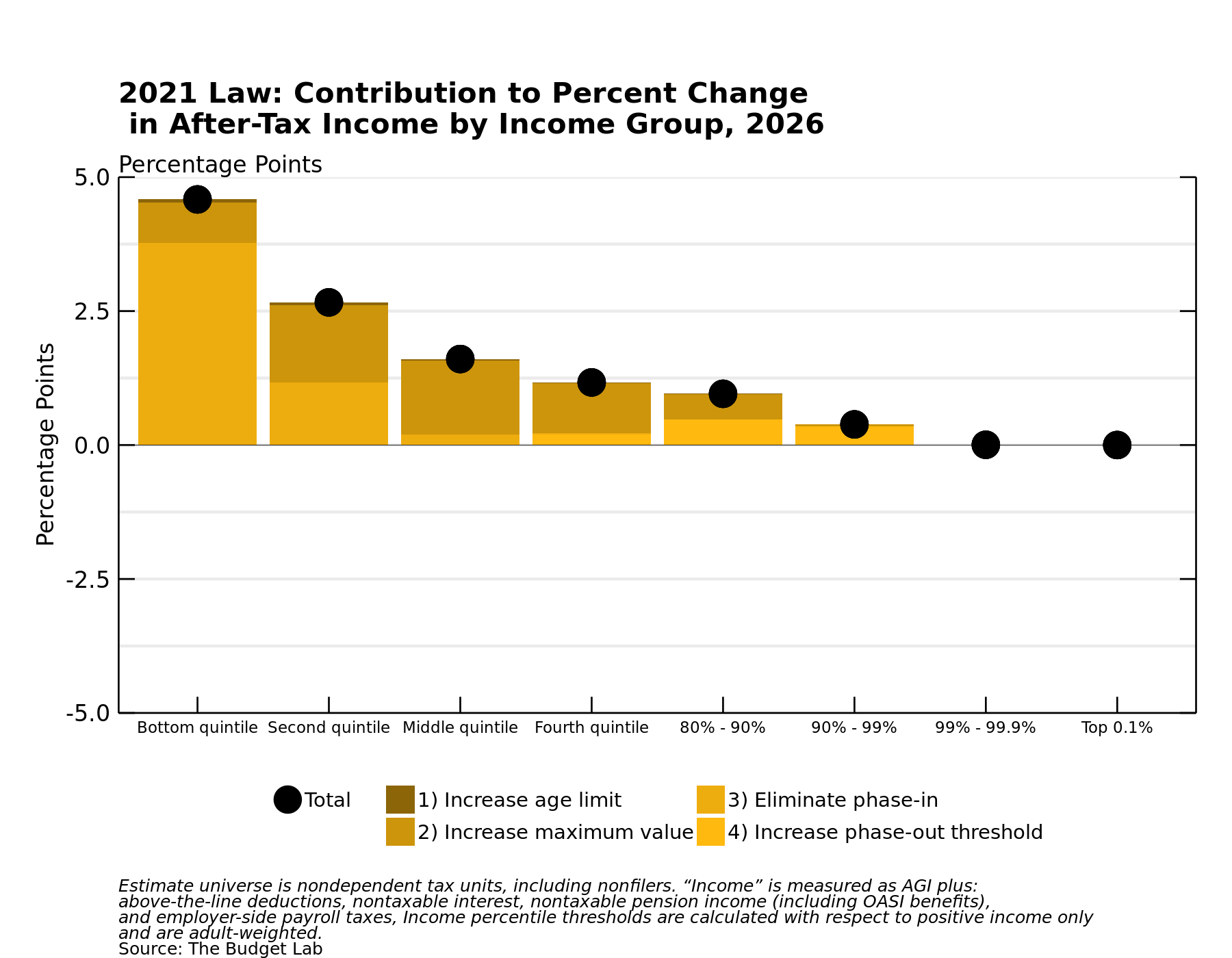

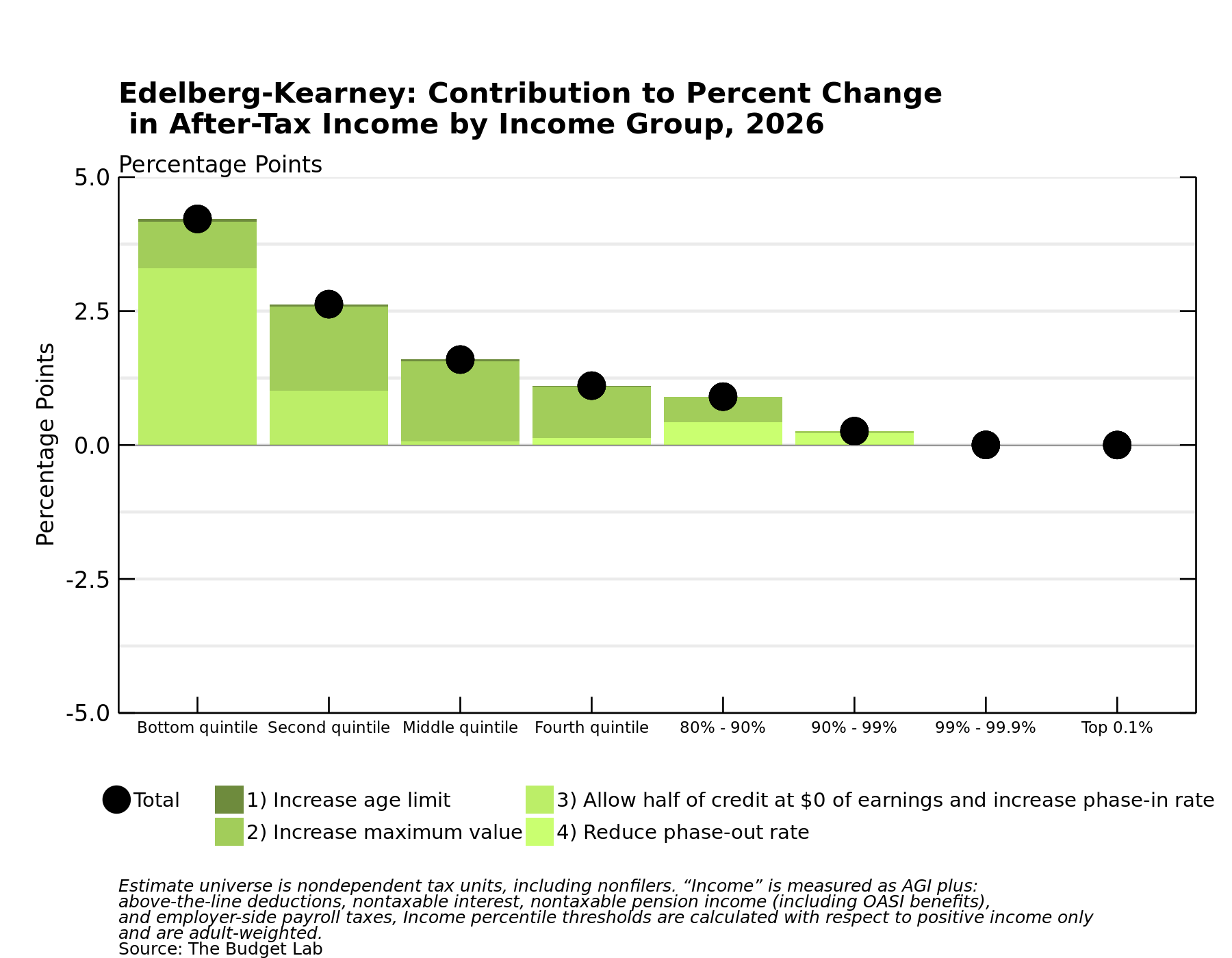

- The FSA, 2021 Law, and Edelberg-Kearney CTC provisions are broadly similar in their distributional effects. Because the 2021 Law allows the full credit value at $0 of earnings, its bottom-quintile benefits are slightly larger, on average.

- Unlike the 2021 Law or Edelberg-Kearney options, the FSA’s CTC provision offers no benefit to nonworking parents. For the lowest income quintile, this restriction slightly outweighs the larger benefit for children aged under 6.

- The FSA’s pay-for provisions would have different impacts at different income levels. The elimination of the SALT deduction would raise taxes on the top 20 percent of families by income, outweighing any benefits from the larger CTC for this group. The EITC cuts and elimination of head-of-household status offset about three-quarters of the CTC benefit for the bottom quintile, and almost all of the benefit for the second quintile, which would be worse off on average than under Current Policy.

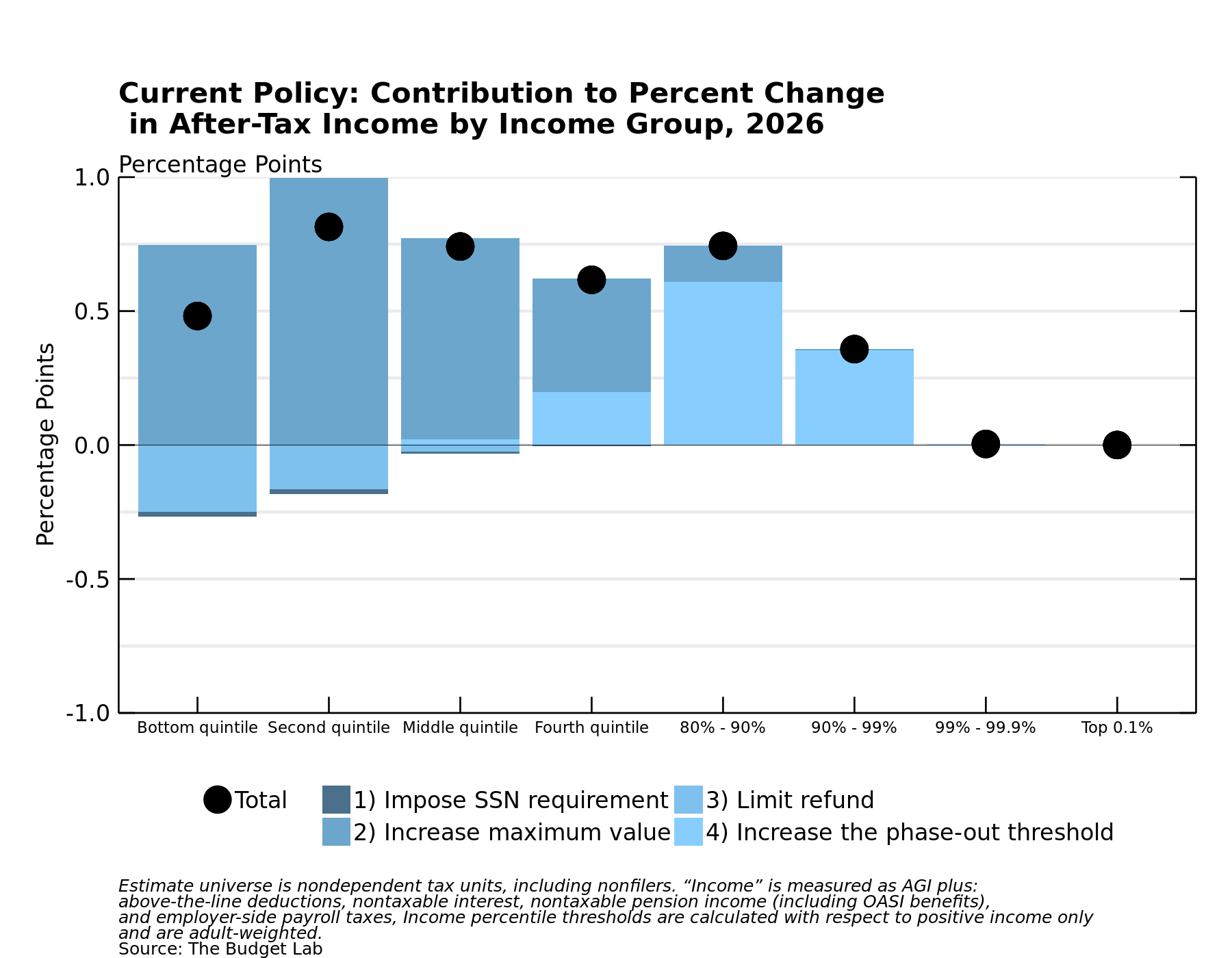

- Because the Current Policy option has the lowest maximum credit value, its effect on after-tax income is smaller at all income levels. Its phase-in structure – wherein the credit phases in at a rate of 15 percent, begins at $2,500 of earnings rather than $0, and is restricted based on income tax liability – limits benefits for the lowest income group. The bottom quintile would only see a 0.5 percent increase in after-tax income, whereas for the next two quintiles, that figure is closer to 1 percent.

Each reform differs in how exactly it delivers tax cuts – or tax increases – to families at each income level. The reforms differ in their treatment of child eligibility, maximum credit values, refundability rules, and phase-out structure. The following four figures break down how each provision contributes to the overall effect on after-tax income in 2026.

The FSA would substantially reduce the earnings threshold for full benefits by increasing phase-in rates. For example, if the FSA retained the current-law phase-in rate of 15 percent, a family with two young children would have to earn more than $56,000 to claim the full credit value; instead, it would reduce this threshold to just $10,000. This provision drives tax cuts for the low end of the income distribution.

These benefits, however, would be partially offset through the FSA’s goal of consolidating child benefits across the tax code. Its EITC cuts would weigh most heavily on the bottom two quintiles, and the elimination of head-of-household status would slightly raise taxes for those ranked 20th to 90th in income percentile. The CDCTC is a relatively small credit under current law, so its elimination does not meaningfully contribute to overall changes. Finally, the SALT deduction elimination drives tax increases for the top quintile – especially those at the very top, for whom the inability to deduct state and local taxes represents a large federal tax increase.

For Current Policy, the largest driver of tax cuts is the increase in the CTC credit value from $1,000 to $2,000. This option’s limitation on refunds for those without sufficient tax liability is a drag on overall benefit to the bottom two quintiles – groups that, under current law, generally have little or no income tax liability. The increase in the phase-out threshold generates benefits for upper-middle class families who are phased out under current law.

A decomposition of distributional impact of 2021 Law reveals that full refundability is the key to delivering benefits to low-income families, a group that is largely shut out from the Current Law CTC because of its phase-in structure. As is the case under Current Policy, those in the top quintile benefit only because the AGI phase-out threshold rises to $400,000 ($200,000 for non-joint returns) from $110,000 ($75,000).

The Edelberg-Kearney proposal highlights that partial refundability and a faster phase-in rate would retain most of 2021 Law’s benefits for low-income families, most of whom have some amount of earnings, while incentivizing work. (For example, the two designs are identical for a low-income, one-child family once earnings reach $6,000). Edelberg-Kearney's phase-out structure, which begins at the same current-law threshold but reduces the credit value more slowly, extends some fraction of the full CTC value to upper-middle class families, who under current law are entirely phased out.

We emphasize again that it is difficult to compare the full FSA plan, which includes pay-fors, to the other three options, which do not. A full accounting would incorporate all possible impacts of deficit financing and how that could impact taxpayers across the income spectrum. The Budget Lab does not attempt this exercise at this time.