June Jobs Day Preview: Flashing “Trend”, Not “Recession”

The June U.S. employment report comes out this Friday at 8:30am ET. Private sector analysts expect that the U.S. added 189,000 payroll jobs in June—lowering the three-month moving average to 209,000—and that the unemployment rate stayed at 4.0%.

Some observers have grown anxious about cooling labor market data in recent months. This anxiety is understandable, because the unemployment rate—probably the best single historical recession indicator we have—has risen modestly over the past year and half. It is about 0.4 percentage points above its prior low over the past 12 months. Such a deterioration is close to what the U.S. has seen at the outset of prior recessions. Under an empirical economic observation dubbed the Sahm Rule, post-World War II U.S. recessions have almost all been associated with the unemployment rate rising 0.5 percentage points above its prior 12 month low.1 While it is unlikely that the June unemployment rate could rise enough to trigger the Sahm Rule, the trend of an unemployment rate slowly creeping upward is causing worry.

But other labor market data complicate this picture because they are much stronger and therefore less suggestive of an impending recession. A June read of +189,000 to payroll employment would be a solid pace by pre-pandemic standards and well above the job losses typical of the opening months of a recession. While the hires rate has declined recently and is below pre-pandemic levels, so too is the layoffs rate, which is among the lowest it’s been in its 23 year history. As The Budget Lab highlighted in a prior Jobs Day preview, the prime-age (25-54) employment-to-population ratio remains high by historical standards and (as of May) is above its pre-pandemic level. Perhaps most importantly, the best canary-in-a-coalmine warning of a recession we have—weekly unemployment insurance claims—show no signs of a recent surge: initial claims throughout the calendar year of 2024 have been coming in at rates consistent with what we saw in 2018, 2019, and 2023.

The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), the organization that officially determines the dates of U.S. business cycles, uses six monthly economic measures to determine recessions. These include payroll and household employment, both included in the jobs report, as well as real (inflation-adjusted) income, real consumer spending, real wholesale and retail sales, and industrial production.

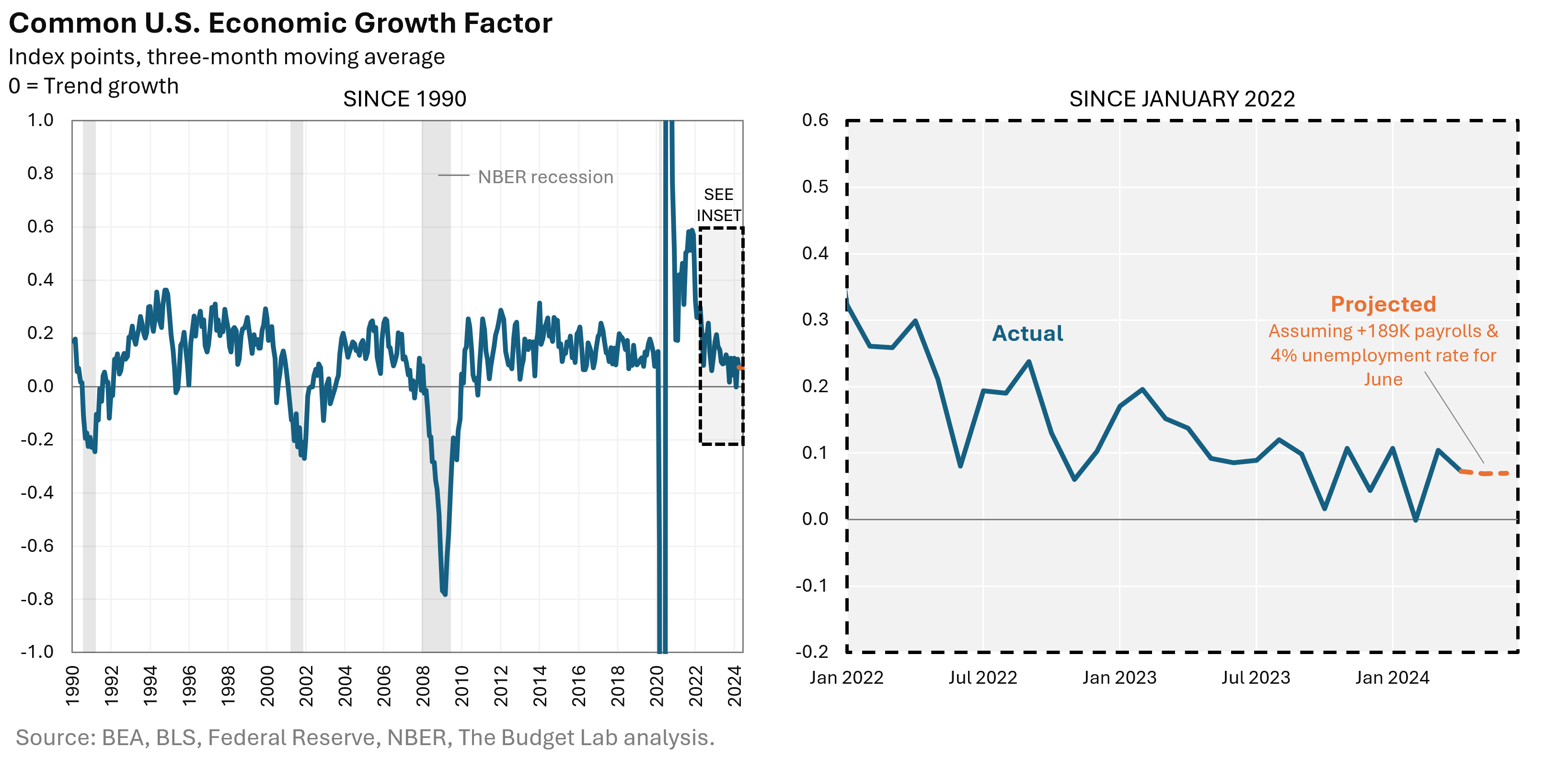

Taken as a whole, these six measures paint a different picture: that the U.S. economy is in the neighborhood of growing at trend right now, not falling into a recession. The figure below summarizes the six NBER measures using a dynamic factor model, which is a statistical technique for teasing out hidden commonalities between different economic data series. The blue line is the common factor underlying all six NBER metrics. Positive values signal that the six measures are generally growing above their average historical pace, while negative values suggest they are below their historical average; an index of zero denotes that the NBER measures taken as a whole are around their trend growth pace. Historically since 1990, NBER has called recessions when the six metrics show decisively below-trend growth (left panel, blue line falls and stays below 0). But that hasn’t been the case recently: the pace of economic growth has certainly been cooling, but it’s been stabilizing at around historical average paces of growth (right panel, blue line is around and even slightly above 0). This remains true if the June jobs report comes in in line with expectations (right panel, orange dashed line).2

The United States typically isn’t at or even close to full employment, so a labor market like today’s—a blessing to so many workers—is extraordinary and uncertain. Economists and policymakers need to be cautious, sober, and humble about the risks to this labor market. Not all labor market metrics look strong anymore, and history shows that labor data can deteriorate remarkably fast. But caution goes both ways in the face of uncertainty. Behavior that might once have been a sure-fire sign of an impending recession, such as a drift up in the unemployment rate, might have other explanations in a full employment economy that we simply have less experience observing. There are other extraordinary factors at play too at the moment, such as immigration, which we mentioned in a prior Jobs Day preview may be boosting the breakeven pace of payroll growth.

So in summary, the data overall are flashing “trend” at the moment, not “recession”. That doesn’t mean that there is no chance of a recession over the horizon—trend is just a stop on the way to a recession after all. It also doesn’t mean no chance of negative surprises—economic data are measured with error and are often volatile, so the closer the truth is to trend, the likelier it is that a single month of a measure might come in negative. But the growth slowdown across the U.S. economy so far has the hallmarks of a mostly positive story: not a downturn but a soft landing.

Footnotes

- More precisely, the Sahm Rule holds that in the US, NBER recession starts are associated with the three-month moving average of the unemployment rate first exceeding 0.5 percentage points of its own prior 12-month minimum.

- We also simulated our dynamic growth factor model if payroll employment growth were revised down by -50,000 a month beginning in April 2023 as a result of annual benchmark revisions. The resulting factor is only slightly weaker (a few hundredths of an index point) and the qualitative conclusions are unchanged.