CTC Expansion Can Take Many Forms, But Full Refundability is Best for Low-Income Families

With individual tax provisions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) expiring, many see an opportunity for expanding the Child Tax Credit (CTC). Notably, the TCJA doubled the maximum credit amount and began phasing the credit out at a much higher income level—changes that are due to expire at the end of 2025.

One option for policymakers is to simply extend the TCJA’s changes. But options for increasing dollars spent on the CTC abound, each producing differential effects on the households that receive the credit. As a result, policymakers discussing the prospect of expanding the CTC must be precise about what they mean. This blog explores the full range of possibilities and their likely effects on affected families. We conclude that the “expansion” providing the biggest bang for buck in improving the wellbeing of the poorest children is making the credit fully refundable.

How can policymakers “expand” the CTC?

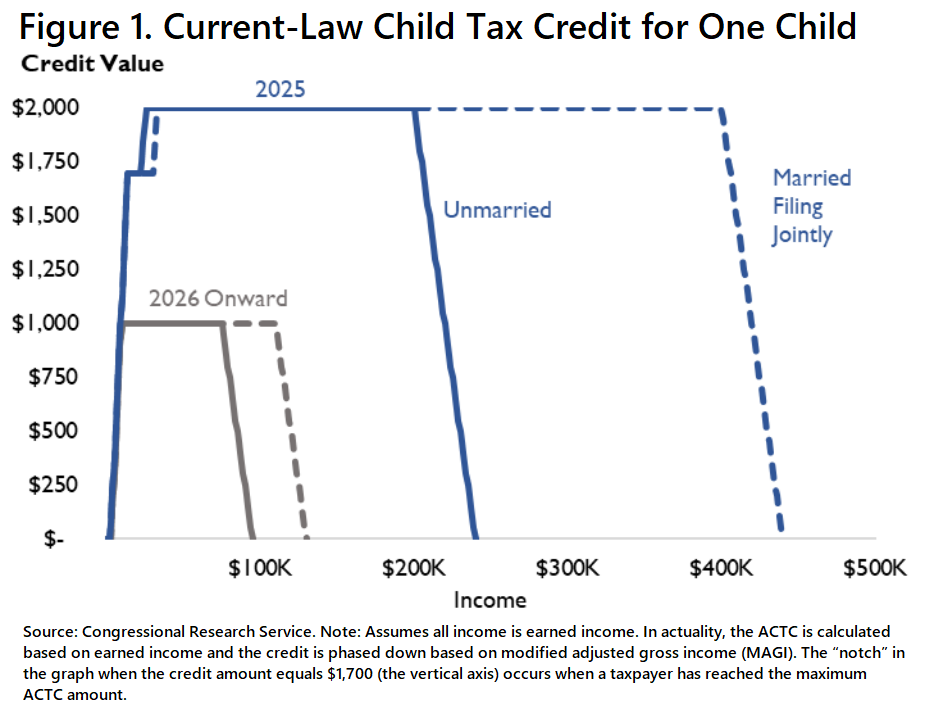

CTC expansion can mean many different things because there are many dimensions along which the CTC can be expanded. The trapezoidal design of the credit provides policymakers with many adjustable levers. Under current law, the credit offers a maximum amount of $2,000 to each child under seventeen years old. This is the top of the trapezoid in Figure 1, which plots the credit paid for a household with one child against household income courtesy of the Congressional Research Service. The credit phases in beginning at $2,500 of earnings at a 15% rate—the left upward slope of the trapezoid. That means that a household must have earnings of at least $2,500 to qualify for any amount of CTC; each dollar of earnings above this minimum threshold generates an additional $0.15 in credit. The credit then phases out at a 5% rate beginning at $200,000 in adjusted gross income (AGI) for single filers and $400,000 for married filers—the right, downward slope of the trapezoid. This means that a taxpayer with one child is no longer eligible for any amount of the CTC with $240,000 in AGI if single, $440,000 if married. Finally, although the maximum credit amount is $2,000, only $1,700 is “refundable,” or available to be paid back to taxpayers without any positive income tax liability.

Given this structure, the most obvious way to expand CTC benefits is to increase the maximum value of the credit. For example, a few proposals suggest raising the maximum value from $2,000 per child to $3,000. Increases in the maximum value of the CTC puts additional dollars in the pockets of households who already receive the credit. This may support additional household spending and saving, and since the credit is not indexed to inflation, increases in the credit’s maximum value may also help families offset recent increases in the cost of living. However, increases in the maximum CTC value do nothing to expand the universe of CTC beneficiaries. Returning to the figure described above, the trapezoid gets taller, but not does not widen the income levels over which a benefit is provided.

Additional benefits can be provided specifically to lower-income families by adjusting the phase-in rate and range. A faster phase-in rate increasingly makes the full $2,000 credit amount available to families with very low levels of earnings, especially if it does so on a “per child” basis. The Family Security Act 2.0, sponsored by former Senator Romney, includes a proposal to phase in the CTC over the first $10,000 of earnings rather than the first $15,833. Meanwhile, Wendy Edelberg and Melissa Kearney propose a phase-in range of $0 to $6,667 by starting the phase-in at $0 using a 30% rate. This would make all families with any amount of earnings eligible for the credit, up to the phase-out threshold. Edelberg and Kearney additionally suggest scaling back CTC benefits to higher income families, phasing the credit out beginning at $110,000 in AGI for single filers and $240,000 for married filers.

These proposals would deliver benefits for families with especially low levels of earnings. A higher phase-in rate makes the left side of the trapezoid steeper, so that low-income families can access the highest level of benefits quicker. Lowering the level of income at which the phase in begins shifts the bottom-left corner of the trapezoid to the left. This delivers the CTC to additional families, but only at a very narrow income band, and offers them a benefit that is a fraction of that low level of income. Similarly, households benefit from a steepening of the phase-in only to a limited extent, since the additional benefit is merely a percentage of household income. A family with one child and $10,000 in earnings receives a $1,125 CTC under current law; doubling the phase-in rate makes this family eligible for the full $2,000 credit.

However, this family will not receive this full credit amount due to the last design feature of the current CTC, limited refundability. A family with $10,000 in earnings and no other income will not owe any positive tax liability—all their income will be swallowed up by the standard deduction. As a result, all of the family’s CTC will be received in the form of a refund. But the refundable amount of the CTC is capped at $1,700, denying this family $300 of credit to which it would otherwise have been entitled. While this example illustrates that benefit expansions targeted at low-income households achieve little without full refundability, partial refundability is a problem under current law CTC parameters as well. Nearly 20 million children currently fail to receive the full credit amount because their families earn too little.

Rather than tweaking the slope or endpoint of the CTC phase-in, a way to bring low-income families up to the full credit amount is to shift the entire left side of the trapezoid upward. This is what full refundability and phase-in elimination (the combination of which is often called “full refundability”) would do. The possibilities of full refundability are well illustrated by previous CTC reform efforts that embraced—or limited—the refundable feature of the credit.

Tax Cuts and Jobs Act

The TCJA introduced two major changes to the CTC, neither of which significantly addressed the refundability question. First, the TCJA increased the maximum benefit of the CTC. As we have seen, however, maximum credit value increases fail to help the lowest income families unless the entire credit can be accessed at low levels of income and provided as a refund to families without positive tax liability. Moreover, even for higher income families, the added benefit from the CTC was offset by the TCJA’s elimination of personal exemptions, which previously provided a per-person deduction for each household member.

The TCJA only moderately adjusted the structure of the CTC for families on the lower end of the income distribution, lowering the earnings level at which phase in begins from $3,000 to $2,500 and increasing the refundable portion from $1,000 to $1,400. But it benefited families at the other end of the distribution, increasing the income level at which the credit phases out from $110,000 to $400,000 for married filers and $75,000 to $200,000 for single filers. The benefit of this modification entirely accrued to higher income families, such that families who previously earned too much to qualify for any amount of credit now receive the full amount.

American Rescue Plan Act

Congress took a very different approach with the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) a few years later. Like the TCJA, ARPA boosted the CTC’s maximum value up an additional $1,000. But ARPA pared back expansions to higher income households by accelerating the credit’s phase out. Furthermore, ARPA combined full refundability with elimination of the credit’s phase in. As a result, every single family with AGI below $75,000 was eligible for a $3,000 per child credit. No longer did families fail to receive the full credit—or any credit at all—because they did not earn enough. These aspects of the ARPA CTC are widely credited with achieving unprecedented reductions in child poverty in the United States.

ARPA also experimented with other aspects of the CTC beyond the basic structural features discussed above. Through full refundability and elimination of the phase in, ARPA concentrated the benefits of the CTC on low-income families. It further concentrated benefits on families with young children by providing an additional $600 for each child under age six. There are a few arguments for increasing benefits for families with young children. First, young children may generate unique expenses, such as daycare. Second, parents with young children are likely to be earlier in their careers and therefore earning less than their counterparts with older kids. And third, the social benefits of providing benefits to young kids may be especially high.

Following ARPA, Wendy Edelberg and Melissa Kearney propose a $600 bonus for each child under six. The Family Security Act 2.0 would provide a $1,200 bonus for this group of young children.

Conclusion

While significant, ARPA’s changes to the CTC were temporary, only lasting for 2021. Meanwhile, the TCJA’s changes remain in effect, though due to expire at the end of the year. As policymakers contend with this impending CTC cliff, the differences between the TCJA and ARPA approaches to CTC expansion illustrate the range of possibilities available to them. Precision is therefore required in discussing potential expansions to the CTC. For those seeking to prioritize children in the lowest-income families by modifying the CTC, making the credit fully refundable is the most powerful lever for change.

Footnotes

- This expansion for higher-income families was designed to offset the loss of dependent exemptions under the TCJA.