How Would Fundamental Tax Reform Affect the Time Burden of Filing Taxes?

Key Takeaways

-

In a recent Brookings Institution research brief, William Gale proposes a series of tax reform options designed to simplify the tax code, increase tax progressivity, and be revenue-neutral in 2023.

-

We estimate that the proposed reforms would reduce the average time it takes to file individual income taxes by at least 2.5 hours (a 20 percent decline) and as many as 7 hours (a decline of half), depending on design details and whether TCJA is extended.

-

Fundamental tax reform would increase the estimated share of tax returns that could be pre-filled from about one third to nearly half.

-

Against a current-law baseline, Gale’s proposed reforms would reduce long-term deficits, increase progressivity, and reduce work incentives. Whether children would earn more in adulthood as a result of these reforms varies across design options.

In a Brookings Institution report titled Radical Simplification of the Income Tax (March 2024), William Gale argues that the existing individual income tax is needlessly complex and, as a result, imposes undue compliance costs on taxpayers. These costs take the form of time spent filing returns, money paid to professional tax preparers,1 economic efficiency losses from tax avoidance, and, in Gale’s view, political economy risks associated with notions of unfairness.

In this context, Gale proposes a menu of four reform options with goals of tax simplification, increased progressivity, and revenue-neutrality in 2023. The proposals share several core design features, including base broadening and the consolidation of tax credits. Preferential tax rates and the alternative minimum tax would also be eliminated. The proposals vary, however, on the precise degree of progressivity – and whether a new value added tax is used as a revenue raiser.

In addition to budgetary and distributional estimates for each proposal, Gale offers qualitative descriptions of how each reform would reduce tax complexity. We add to his analysis by generating quantitative tax burden estimates – specifically, how the proposals would affect the time burden of filing taxes and the number of families who could benefit from pre-filled tax returns. We also offer a more general budget score of the proposals, highlighting their budgetary, distributional, and microeconomic effects.

Reforms

This section briefly describes the provisions of Gale’s proposals. All four reform options share a core set of provisions:

- Repeal itemized deductions. All existing current-law itemized deductions, including the mortgage interest deduction, the deduction for state and local taxes, and the charitable deduction would be repealed. All filers would instead take the standard deduction, reducing the amount of recordkeeping and paperwork involved with filing taxes.

- Repeal the QBI deduction. The deduction for Qualified Business Income (QBI), which reduces the tax rate on certain forms of pass-through income by up to 20 percent, would be permanently repealed. This deduction adds complexity through its rules about which kinds of income qualify for the benefit.

- Tax capital gains and dividends at ordinary rates. All capital income, including that which under current law faces preferential rates, would be included in ordinary taxable income. Current-law preferential rates require additional calculations and encourage inefficient income shifting into tax-favored categories.

- Repeal all personal tax credits. The proposals would repeal the Child Tax Credit (CTC), the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit (CDCTC), credits for higher education expenses, the Savers Credit, and the Credit for the Elderly or the Disabled. These credits overlap in their goals: for example, both the CTC and EITC give tax relief to families with children and do so in a way that encourages work. They also involve complicated eligibility rules which lead to high rates of improper payments.2

- Introduce a new individual work credit. In place of the EITC, the proposals would introduce a new work credit based on individual, rather than tax unit-level, earnings. The credit would be worth 20 percent of earnings up to a maximum value of $4,000 – in other words, it would phase in up to $20,000 of individual earnings. Then, it would phase out at a rate of 20 percent until earnings reach $40,000. This provision is designed to maintain the “labor force participation bonus” associated with current-law low-income tax credits, but to do so in a way that reduces complexity, removes marriage penalties, and separates labor market policy from child benefit policy.

- Repeal Head of Household filing status. The Head of Household filing status, which offers preferential brackets, credit values, phaseout ranges, and more to certain unmarried parents, would be repealed, meaning that the filing status determination component of preparing a tax return would be made simpler.

- Repeal the AMT. The proposal would eliminate the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT), a parallel tax system that requires some filers to do their taxes twice and pay the greater of the two liabilities. This provision would lessen the time burden of filing by reducing the number of forms that a filer must fill out.

Note that Gale designed these reforms to be revenue-neutral against current policy in 2023, under which the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) is law. Scored against a current-law baseline after 2025, the revenue impact is different. For example, the QBI deduction is repealed beginning in 2026 under current law, so that provision raises no revenue. We assume that new tax provisions are indexed to inflation. Our budget analysis below covers these issues in more detail.

Simplified Income Tax

The first reform option is titled Simplified Income Tax (“Simple”). In addition to the core provisions described above, it would add a new $1,000 refundable personal credit for each family member. This credit, akin to a small universal basic income (UBI), is designed to generate progressivity and offset part of the loss of the CTC.

Modified Simplified Income Tax

The second reform option, titled Modified Simple Income Tax (“Modified”), is a variation on the “Simple” option. It addresses progressivity concerns from the first option which, through its consolidation of tax credits, would leave some lower income families with children worse off than under current law. These families are beneficiaries of many provisions under current law and the new personal and work credits do not fully replace current-law benefits. To address this effect, the personal credit value is increased to $2,000; to maintain revenue neutrality, a phase-out is added wherein the credit tapers at a rate of 40 percent beginning at $36,000 of income for single filers and $72,000 for married filers. This modification illustrates a core tradeoff in designing tax returns: the desire to limit the number of “losers” in a reform often adds complexity through phase-outs, base narrowers, and other kinds of targeting.

Back to the Future

The third reform option, called Back to the Future (“Future”), raises the personal credit value to $2,800 per person (with no phaseout). It also further simplifies the income tax by increasing the standard deduction to $50,000 (single)/$100,000 (married) and replacing current-law tax rates such that 25 percent is the lowest rate. The increase in the standard deduction would eliminate the need for millions of families to pay individual income tax.

To offset the revenue shortfall associated with these changes, the proposal would also institute a new 10 percent value added tax (VAT), a type of administratively efficient consumption tax found in most other countries. The VAT would apply to a broad base of consumption.

Universal Basic Income

The fourth and final reform proposal, called Universal Basic Income (“UBI”), maintains the 10 percent VAT from the prior option but opts for a larger personal credit ($3,900 per person) instead of making changes to rates and the standard deduction.

The parameters of each reform are summarized in the table below.

Effects on the Time Burden of Tax Filing

What makes a tax code “simple”? How do we know if a tax reform reduces tax complexity?

While simplicity in the tax code is a multi-dimensional concept, one quantifiable measure is how much time it takes taxpayers to comply with the law. Understanding the tax law, keeping records of economic activity, and filling out forms are activities which cost time and resources. Simpler tax systems tend to place less time burden on taxpayers. This section presents quantitative estimates of how each reform proposal would affect the time burden of tax filing, estimated using our tax burden model.

Under current law, the estimated average time to file an individual income tax return is 13 hours in 2025. Time burdens vary widely with income: as is shown in Table 2, tax units in the top income decile take more than 23 hours on average to file taxes, while those in the bottom half of the income distribution take fewer than 13 hours on average. This difference is largely attributable to differences in the composition of income, as higher-income returns are more likely to report capital gains, business income, rental income, and other forms of income which require more recordkeeping due to limited third-party reporting and withholding. These types of income require an additional 6 hours of filing time, on average. Higher-income filers are also more likely to itemize deductions, owe AMT liability, or claim the QBI deduction, all of which require additional time to file. These factors outweigh the fact that lower-income filers face additional time burdens from certain targeted credits like the EITC.

The “Simple” reform option would reduce the average time burden by about 2.5 hours. The largest drivers of this estimated reduction are the repeal of itemized deductions, QBI deduction, and the AMT. The repeal of all personal tax credits, preferential rates, and HoH filing status also reduce filers’ time burden. We estimate that the “UBI” option, which is a very similar reform outside of its VAT, would have the same effect on time burdens at the individual level.

The “Modified Simple” option would further reduce the average time to file by an additional 20 minutes relative to the Simple option. This reduction reflects the fact that the personal credit phases out under this option and thus fewer filers would need to fill out the requisite form.3 The difference between these reforms underscores our earlier point that time burden is only one dimension of tax simplicity. While phase-outs eliminate the need for some taxpayers to file certain forms, they add complexity by creating new eligibility rules and by generating implicit marginal tax rates (of which taxpayers may not be aware when making economic decisions).

The “Future” reform option is distinct from the other three reform options in its large expansion of the standard deduction. This provision is designed to remove the need for anyone with less than $50,000 in income ($100,000 for joint returns) to file tax returns. As such, this reform option results in the largest estimated reduction in time burden, a benefit that is concentrated lower- and middle-income groups by design. We estimate that the average time to file an individual income tax return would fall by more than 5 hours under this reform.

For 2026, we project that average time to file under current law will be 14.2 hours. This average is higher than that of 2025 and reflects the expiration of several TCJA provisions which reduced time burdens, such as limitations on itemized deductions, the higher standard deduction, and a higher AMT exemption. The reforms presented in this analysis would reduce the time to file by an estimated minimum of four hours over current law in 2026, with the Future option cutting average time burdens by half.

These numbers reflect the burden of filing the individual income tax only. But both the “Future” and “UBI” proposals would add a VAT as part of the revenue-raising mix. A VAT is a kind of consumption tax levied at each stage of the production process. While VATs are understood to be a comparatively administratively efficient way to raise revenue, the introduction of a new tax system does impose an additional time burden through its recordkeeping and filing requirements. However, this new burden is borne by businesses rather than individuals.

How much of the time savings from income tax simplification would be shifted to businesses under the new VAT? We can calculate a back-of-the-envelope estimate based on data from other countries. While no country imposes a VAT as broad and simple as Gale’s proposed design, the time burden of a VAT in peer countries with relatively simple designs ranges from 15 to 30 hours per year; refer to the appendix for additional details on these estimates. About 35 million businesses file taxes in the United States.4 The proposed VAT, then, would increase time burdens on businesses by between 525 million and about 1 billion hours per year. These figures can be compared to the estimated total individual time savings in 2026, which ranges from 670 million hours under the “UBI” option and 1.2 billion hours under the “Future” option. Note that most of the 35 million businesses are sole proprietorships, complicating the interpretation of these reforms as shifting time burden from individuals to businesses. Still, an overall per-business average VAT time burden estimate masks the fact that smaller businesses (including sole proprietorships) would have lower-than-average time burdens.

Number of Potential Pre-filled Returns

As mentioned in previous work, there are some filers whose only income is that which is subject to extensive information reporting already – namely, W-2 wages and Social Security benefits. Filers who do not report other kinds of income and do not itemize their deductions are prime candidates for a system of pre-filled returns, wherein the government could use information it already has available to pre-populate the Form 1040 on behalf of certain taxpayers with simple tax situations. These taxpayers would then have the choice of affirming the IRS’s estimate or filling out their own return. This kind of “return-free filing”, the goal of which is to reduce the time burden of taxes faced by individuals, has precedent in peer countries and would require substantial administrative changes from the IRS. In the report, Gale discusses this kind of system as a potential policy goal which could be made possible by tax simplification.

The reform options presented here would substantially increase the estimated number of filers eligible for pre-filled returns. This effect is due to the elimination of itemized deductions in each option. Under current law, we estimate that almost 40 percent of filers would be candidates for pre-filled returns in 2025 while just over 36 percent would be candidates in 2026. In both 2025 and 2026, each reform would increase the share of eligible pre-filled returns to almost 50 percent. This figure includes those who may not need to file a tax return whatsoever because the standard deduction exceeds their income.

Effects on Other Indicators

In this section, we present our standard suite of budget scorekeeping metrics for Gale’s proposals.

Budgetary Effects

Gale’s reforms were designed to be revenue-neutral with respect to current policy – that is, against a tax law baseline that includes TCJA’s individual tax cuts. Under current law, however, these tax cuts expire at the end of 2025. This means that, against a current-law baseline (as is standard in budget scorekeeping convention), Gale's packages are not revenue-neutral ex-ante. Whether this baseline difference increases or decrease budget costs is an empirical question: some provisions (such as the repeal of itemized deductions) raise more revenue against a current-law baseline, others (like the repeal of QBI deduction repeal or the standard deduction increase) raise less or are more expensive.

The table below presents estimated budgetary effects of each proposal scored against our current-law baseline.

We estimate that the set of provisions common to each reform option would increase revenues by more than half a trillion dollars annually after the expiration of TCJA. Itemized deduction repeal and the elimination of preferential tax rates on dividends and capital gains are the largest contributors.5 This estimated revenue gain is somewhat larger against current law than against current policy. All else equal, this difference in baselines pushes Gale’s reform options from revenue-neutrality into deficit reduction.

A portion of this revenue is invested into a small UBI under each reform option. The share-of-GDP cost of these UBI provisions falls over time as productivity growth exceeds population growth. We estimate that the two non-VAT plans, “Simple” and “Modified Simple”, would raise around 1-to-1.2 percent of GDP by the third decade of enactment.

The other two scenarios, “Future” and “UBI”, also include the introduction of a 10 percent VAT assessed on nearly all domestic consumption in the US. We estimate this new tax would raise more than 4 percent of GDP per year, even after accounting for its negative effects on other sources of revenue.6 Because the Budget Lab assumes that the Fed would allow for a one-time price level increase in response to the enactment of a VAT, we express dollar-amount revenues both in “real” terms (i.e. baseline dollars) and nominal terms. The former presentation allows for a more intuitive comparison to baseline; the latter is helpful for government budgeting, which is generally done in nominal terms. We do not account for any effects of higher prices on government spending, which would somewhat reduce the net budgetary savings from a VAT.

Distributional Effects

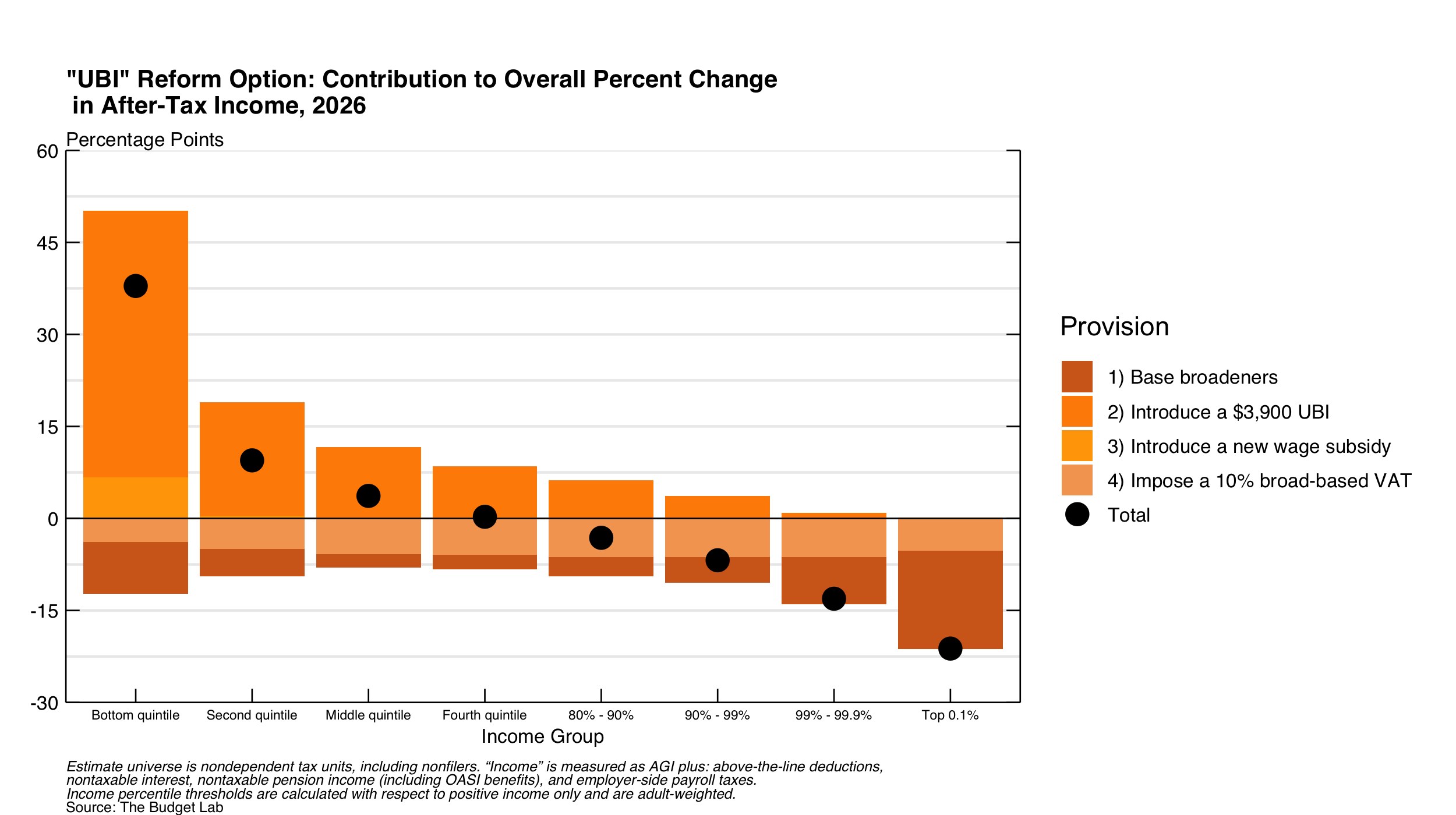

Gale’s proposals would have substantial distributional implications. The figure below shows how each reform option would affect after-tax incomes. Our findings are consistent with Gale’s: each proposal would be steeply progressive, raising after-tax incomes for lower-income families while increasing taxes for upper-middle and high-income households. Progressivity generally varies with the size of the UBI, larger values of which generate sharp relative increases in lower-income families’ after-tax incomes.7

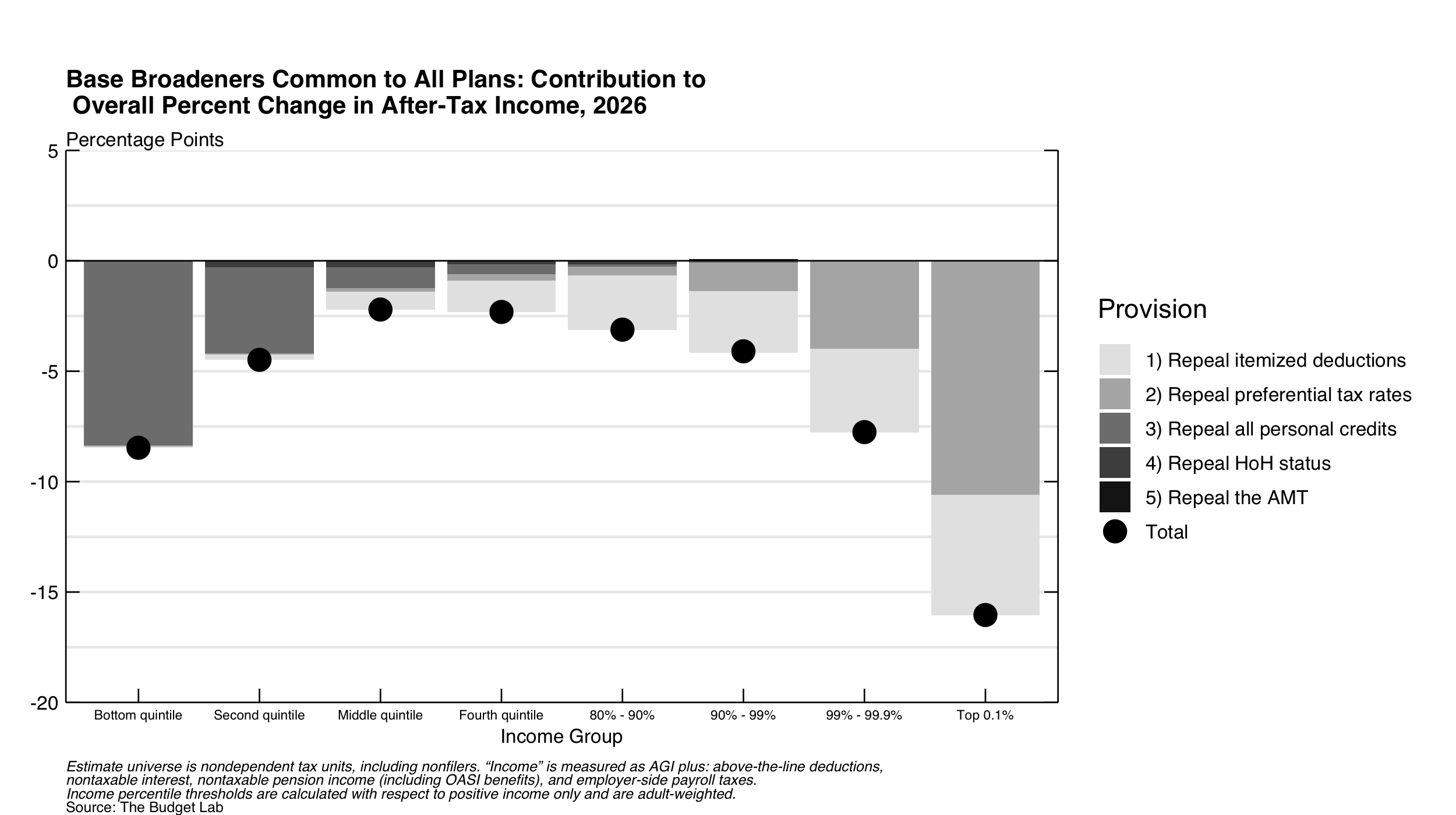

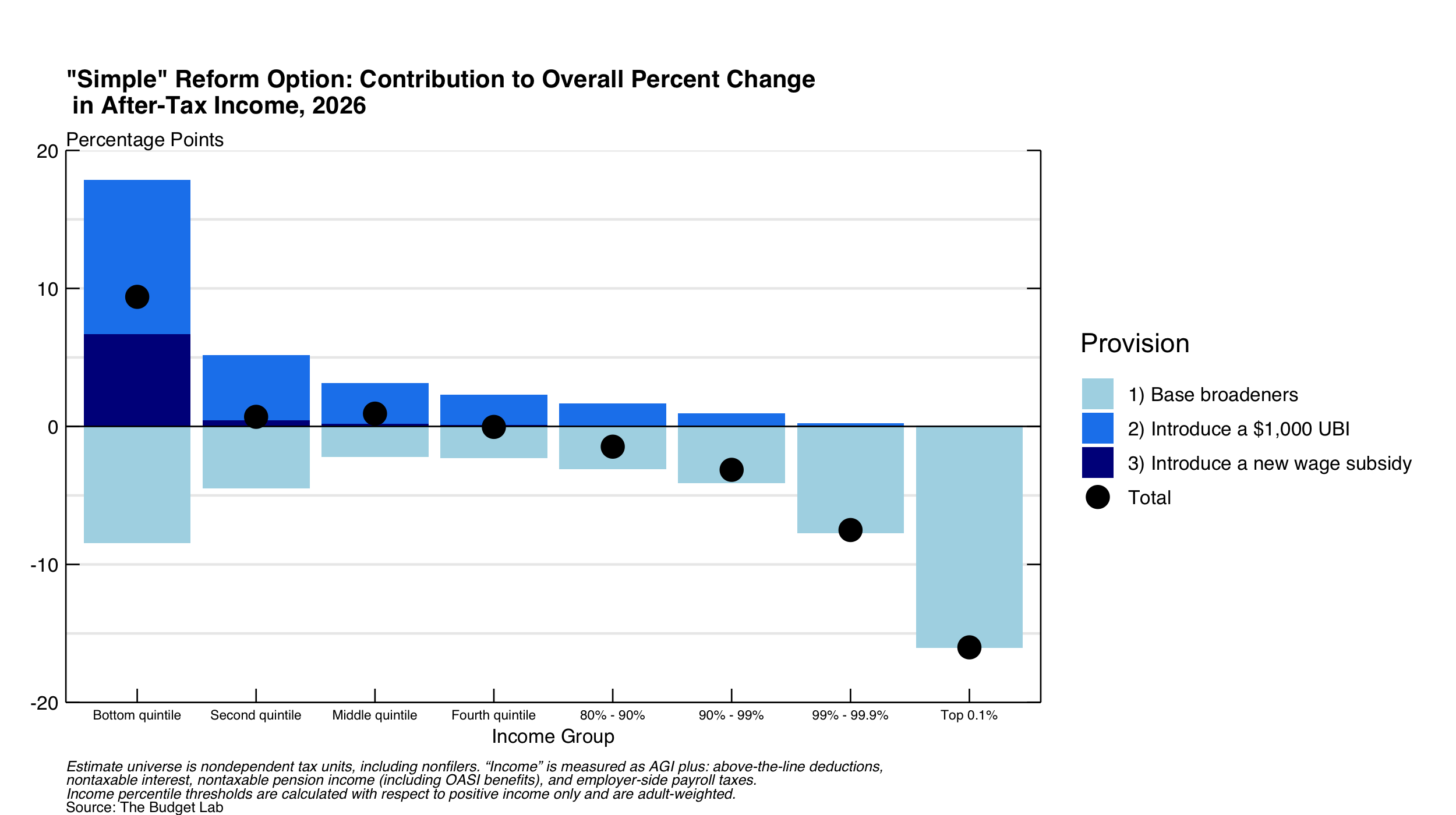

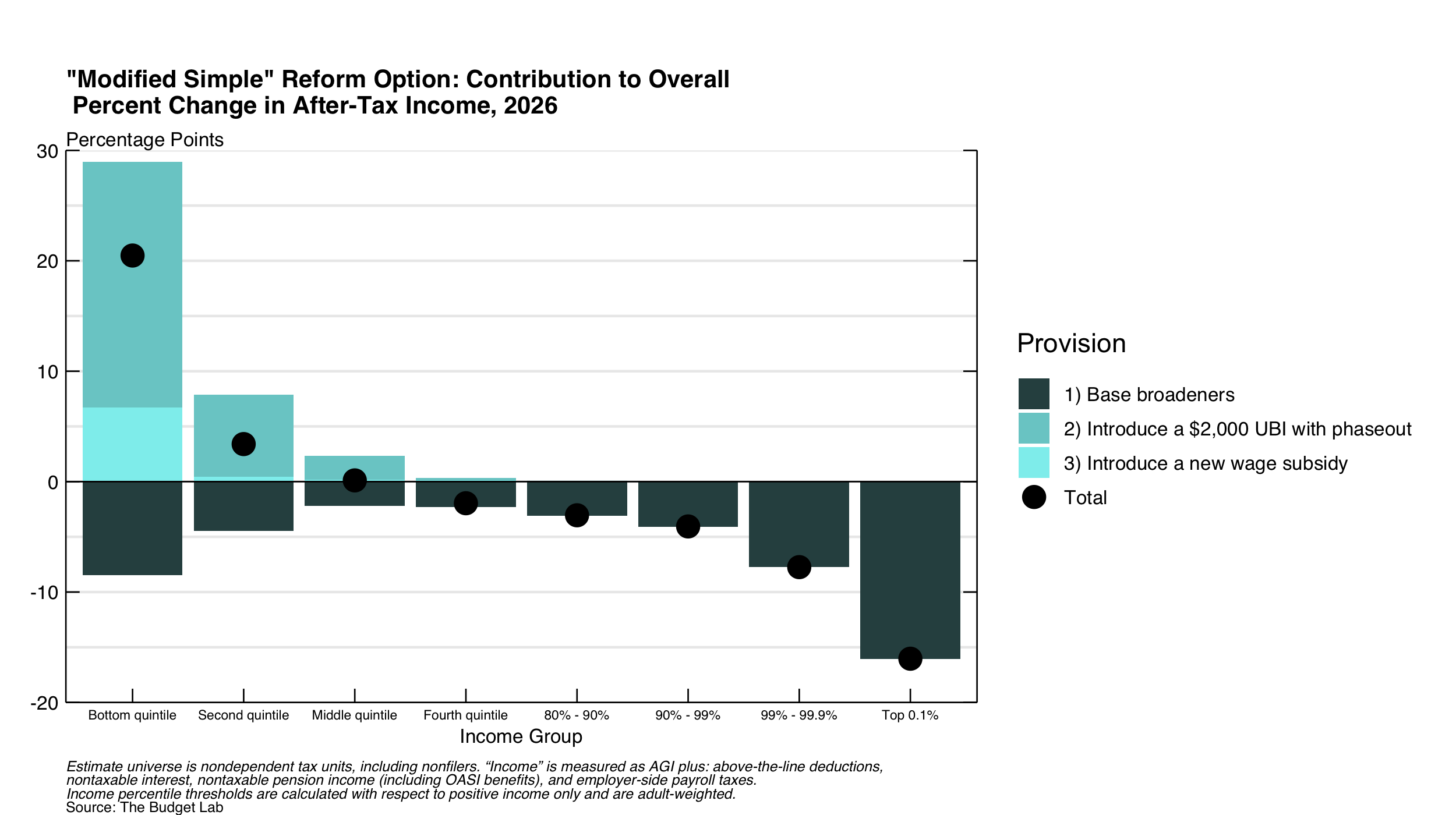

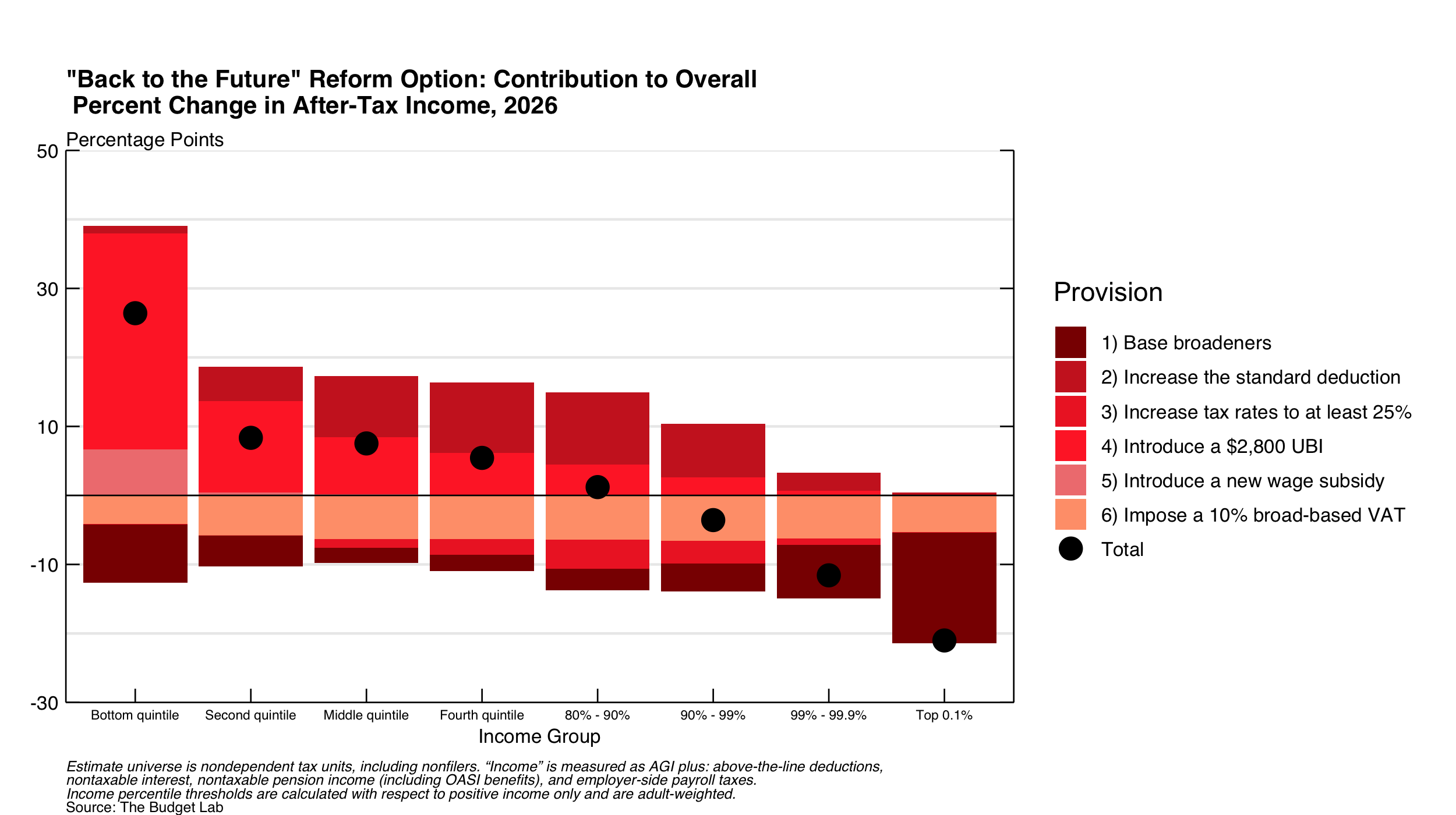

We decompose the overall distributional effects overall into provision-level contributions shown in the figures below. The first of these charts breaks down the effects of base-broadening provisions common to all reform options; the latter four figures show how each proposal’s design difference would stack on top of those common features.

The burden of the proposed revenue-raising provisions would fall disproportionately on low- and high-income households. The loss of itemized deductions and preferential tax rates on dividends and capital gains would generate substantial tax increases on high-income families. (The loss of the QBI deduction has no effect in 2026, as current law already repeals it.) The loss of personal credits, the largest of which are the EITC and the CTC, reduces after-tax incomes most for the bottom two quintiles in relative terms. As shown in the revenue estimates, AMT repeal has a limited effect on liability when stacked after the repeal of provisions it is designed to claw back.

The “Simple” and ”Modified Simple” reforms are designed to offset tax increases from base-broadening measures using the UBI and the wage subsidy. Universal per-person transfers, as in the case with the “Simple” option, are steeply progressive: $1 of tax relief for a low-income family is a greater share of income than for a high-income family. The means-tested version of a UBI in “Modified Simple” adds progressivity by concentrating a similarly size aggregate tax cut among those below a certain income threshold. Note that these are average estimated tax changes; some number of low-income families would still be worse off, especially under the “Simple” option wherein the UBI does not offset the loss of child-contingent benefits for certain parents.8

Both the “Future” and the “UBI” options trade a more generous UBI, which is more expensive from a budget perspective, for a VAT, which raises additional revenue. We estimate that a VAT, in its second year of enactment, would be slightly progressive. This finding, which may challenge common intuitions about the distributional impact of consumption taxes, stems from two factors:

- First, most major elements of the broader tax and transfer system are indexed to inflation. We assume that the Federal Reserve would allow consumer prices to rise in response to a VAT (as opposed to the VAT’s burden being “passed backwards” in the form of lower incomes). A disproportionate share of the bottom quintile’s income stems from transfer programs (including Social Security), most of which are indexed and thus would automatically rise in proportion to a VAT-driven increase in consumer prices. For example, we project that the $3,900 UBI in the “UBI” reform option would rise to $4,300 in 2026 in response to the VAT. This cushion against rising prices contrasts with the expected response in labor income (which would not rise in response to a VAT) and capital income (which would only rise over time as new investments are made), both of which comprise a greater share of income for higher-income groups.

- Second, VATs are more progressive in the immediate years following enactment than they are in the long run when they become regressive. It is widely understood that VATs function as a kind of tax on wealth, burdening returns to “old” (i.e. pre-enactment) investments while exempting the normal return to new investments from tax. In the first year of enactment, all capital income is “old” capital; in the long run, all capital income is “new” capital. Because capital income is skewed towards high-income families, this dynamic means that a VAT will become more regressive over time. A similar “vintaging” effect happens with Social Security recipients. Beneficiaries who retired prior to VAT enactment would see a cost-of-living adjustment for the VAT-driven price increase, whereas those who retire after enactment would see no such adjustment. Thus, over time, a greater share of Social Security recipients, the benefits of whom disproportionately contribute to total income of lower-income groups, would be burdened by the VAT. As such, the VAT’s effect would shift from progressive to regressive over time – our distribution tables in the 30th year of enactment, which can be found in the data download file, show the VAT provision would be somewhat regressive.

We emphasize that quantifying the burden of indirect taxes involves making more assumptions than is required for individual income and payroll taxes. Other approaches, such as distributing the burden in proportion to current-period consumption, would generate a more regressive result. Please refer to our VAT methodology page for a full discussion of these modeling considerations.

A final noteworthy finding is that increasing the standard deduction is less progressive when done in the context of a tax system with no itemized deductions, as demonstrated in the provision-level breakdown of “Future”. Overall, the “Future” and “UBI” reform options are the most progressive, highlighting an established result in public finance that a flat rebate paid for by a tax on consumption is a progressive fiscal program.

Microeconomic Effects

The conventional revenue estimates presented above account for certain types of avoidance behavior but exclude real economic responses. In this section, we analyze how each reform proposal would affect microeconomic outcomes – specifically, parental labor supply decisions and the future earnings of children impacted by these reforms.

Tax policy affects employment through its effects on work incentives. Under current law, the combination of progressive rates, deductions, credits, phase-in ranges, and phase-out ranges create work incentives which vary based on income level, income composition, marital status, parental status, and more. Gale’s simplification measures would eliminate and replace many of these features, generating changes in work incentives as measured by effective marginal tax rates (EMTRs). The figure below shows average EMTRs by income and parental status under current law and each of the reform options.

Current law is characterized by negative EMTRs for low-income parents as child benefits phase in with income. Average EMTRs quickly rise with higher earnings to more than 30 percent for low- to middle-income parents as these benefits phase out and income exceeds the standard deduction. For non-parents, who don’t benefit from the CTC or a more generous EITC, average EMTRs are always positive and rise steadily. In other words: the existing tax system explicitly encourages parents to participate in the labor force.

Gale’s reforms would eliminate the credits that give rise to these dynamics, replacing them with a UBI and an individual-level wage subsidy credit. The UBI has no phase-in, and the wage subsidy phases in at a rate of 20 percent. For parents, the net effect is an increase in EMTRs relative to current law; for non-parents, the net effect is a decrease. That is, for those who are marginally attached to the labor force, parents’ work incentives would be weaker, whereas non-parents' incentives would be stronger.

For workers in the $30,000 to $60,000 range, the effect on work incentives varies by reform option. In this range, current law generates high marginal rates for parents as child benefits phase out. Gale’s reforms, which have no such programs and thus no similar effect, would increase work incentives for this group. The exception is the “Modified Simple” option, which includes a sharp phase out of the UBI and thus creates EMTRs of more than 50 percent. The large standard deduction increases in the “Back to the Future” option means that most workers in this range would pay no income tax and thus face lower EMTRs.

How would these changes in work incentives translate to employment? Our approach to estimating labor supply responses assumes that different kinds of workers are more responsive to tax policy than others – and thus accounts for the fact that Gale’s reforms would have heterogenous effects on low-income, middle-income, parents, and non-parents. We find that, on net, each reform would reduce employment by about 500,000 workers, about 0.3 percent of the labor force. The “Modified Simple” reform, with its strong disincentive effects created by the UBI phase out, would induce a slightly higher number of labor force exits; “Back to the Future”, whose large standard deduction means that married workers face no income taxes until their income exceeds $100,000, would induce a slightly lower number of labor force exits.

Another potential impact of tax policy is its effects on the future economic outcomes of children. By partially determining the amount of financial resources available to families with children, tax policy may might impact later-life outcomes through various channels including improved nutrition and health, better education, the ability to move to higher-opportunity geographic areas, and more. We simulate these effects using a parsimonious approach based on observed correlations between parents’ incomes and children’s future incomes. Our strategy maps changes in today’s income caused by a tax reform to changes in future earnings, with effect sizes varying based on a child’s parent’s rank in the income distribution. A key determinant of how fundamental reform affects future earnings, then, is to what extent it transfers resources from non-parents to parents.

The figure below shows estimated effects on wages in 2054 among workers who were exposed to these reforms as children, organized by parent income rank. We find that the “Simple” reform option would modestly reduce future wages for children who grew up in the bottom quintile. This negative effect stems from the $1,000 UBI and work credit being insufficient to offset the repeal of current-law child benefits, a finding which Gale’s own distributional analysis confirms. The “Modified Simple” reform attempts to remedy this effect and as such would have a negligible impact on future wages. In contrast, the larger UBI values in the “Future” and “UBI” reforms would leave lower-income children better off on average compared with current law. We estimate these children would see a 1.5 percent increase in earnings under the latter reform – an annual earnings increase of about $500 in today’s terms.

Conclusion

Gale’s proposals to simplify the income tax would reduce the time burden of filing taxes for individuals. We find that filers would spend between 2.5 and 7 fewer hours doing their taxes on average, depending on reform details and whether TCJA is extended. These savings would be somewhat offset by a new time burden on businesses via the introduction of a VAT in some options.

Gale’s proposed reforms also underscore the budgetary, distributional, and efficiency tradeoffs associated with fundamental tax reform. Against current law, his proposals would reduce deficits while making the tax code more progressive, though many low-income parents would be made worse off unless the proposed UBI was made sufficiently large. We estimate that labor supply would fall slightly in response to higher average marginal tax rates on labor income for some workers, and that proposals with larger UBIs would boost the future earnings of certain low-income children.

Appendix

Methodology: Model Updates

To estimate average time burdens under different tax reform scenarios, we use a model based on IRS estimates of how long it takes to comply with different parts of the individual income tax code. For example, the IRS reports it takes filers an average of about 6 hours to comply with the requirements of Schedule D. Each major component of the income tax is assigned a time burden “weight” such that, for each record in our tax microsimulation model, we can project the time burden of filing taxes under a given tax reform scenario. These micro-level projections can then be aggregated to generate average and distributional measures of time burden. A full description of the model can be found here; see this report for an example of model results in practice.

Several provisions in Gale's set of reform proposals required us to modify the time burden model. In a previous version of the model, the time burden of these provisions was assumed to be invariant with respect to policy changes – in other words, these provisions were treated as fixed costs of filing. To accurately capture how time burden would fall if these provisions were repealed, we updated the model such that these components are treated as having a marginal time burden cost (rather than a fixed time burden cost).

One such provision is the repeal of Head of Household (HoH) status, a preferential filing status which adds time burden by requiring verification of marital status, dependent relationships, residency, and more. It also generates complexity by adding additional lines on other forms, as different sets of tax parameters apply to HoH filers versus single or joint filers. The IRS provides no information on the marginal time cost of HoH status. We assume that the status verification component of HoH is similar to that of the EITC (34 minutes according to the IRS), which involves similar eligibility rules and affects similar populations. In addition, we add 11 minutes for each form that requires extra information for HoH filers. This 11-minute assumption is taken from the reported time needed for “preparing the form” for Schedule D-1 – a form used for reporting additional asset sales, the time burden of which reflects filling out additional lines.

Another new feature accounts for the elimination of preferential rates on capital gains and dividends. Under current law, filers with income subject to preferential rates are required to compile and report this income separately, a process which involves additional calculations and time. Our assumption is that this time cost is equivalent to the time required to complete the schedule D-1: 59 minutes on average, according to the IRS. Removing the preferential rate structure reduces the time burden by this amount.

The final change we make to account for Gale’s proposed reforms is to treat personal credits as marginal time costs. The IRS does not report estimated time burden for the forms associated with these credits. We assume that each tax credit repealed under these reforms saves 34 minutes per claimant – the same time burden as that of the EITC.

Methodology: VAT Time Burden

To estimate the time burden associated with a VAT, we rely on a World Bank report titled Paying Taxes: The Global Picture. This paper reports the hours per year required to file corporate, individual, and consumption taxes for 175 countries. There is a wide range of time burdens for consumption taxes: while the average time to comply is 140 hours for each business, estimates range from just 8 hours in Switzerland to 1,374 hours in Brazil. This degree of variation reflects policy differences (e.g. credit-invoice VAT vs retail sales tax), differences in tax bases, institutional administrative capacity, and measurement uncertainty. There may also be complementarities in recordkeeping for firms operating in countries with both corporate income taxes and consumption taxes.

For these reasons, choosing an appropriate time burden assumption for Gale's proposed VAT is not straightforward. For peer countries like France, the United Kingdom, and Germany, the estimated time to comply is 24, 25, and 40 hours, respectively. But the VAT proposed by Gale covers a much more comprehensive base, suggesting it would be simpler and thus generate smaller time burdens than the VATs of those countries. New Zealand’s VAT is the most similar to Gale’s proposal. To that end, we assume that the time burden for Gale's proposed VAT would lie somewhere between New Zealand’s 15 hours and the average time burden for VATs in France, the United Kingdom, and Germany (30 hours).

Footnotes

- The IRS recently announced an extension of Direct File, a pilot program which aims to ameliorate these monetary costs by offering free direct filing with the IRS for taxpayers with relatively simple tax situations.

- It is important to emphasize that improper payments are not necessarily fraudulent.

- Our estimates treat all phased-out filers as incurring no time burden. In reality, some filers near the phaseout range would need to determine whether they qualify by filling out certain forms. As such, our burden estimates for provisions which phase out should be understood as lower bounds.

- This number is from the IRS integrated business data made available by the Statistics of Income (SOI) division. The most recent version of the data is for 2015. It is available here.

- Compared with Gale’s budget estimates, we estimate a larger revenue gain from the latter provision because we assume a slightly lower capital gains realization elasticity.

- A VAT is an indirect tax, meaning it creates a wedge between consumer prices and producer prices. Whether this wedge gets resolved as higher consumer prices or lower nominal incomes depends on how the Federal Reserve responds. In either case, the real value of other taxes, which are based on those incomes, would fall in response to the VAT, partially offsetting some of the first-order revenue raised.

- Our model’s definition of income currently excludes most transfer income. This limitation mechanically increases the relative size of tax cuts for lower-income groups.

- Please see the data download file for additional distribution metrics.