New Tax Breaks in the Reconciliation Bill Would Reverse Much of the TCJA's Progress Toward Horizontal Equity

Key Takeaways

-

The reconciliation bill would affect not only the distribution of taxes paid across the income distribution (“vertical equity”) but also the distribution of tax burdens within income groups (“horizontal equity”).

-

While the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) generally improved horizontal equity by reducing tax rate dispersion among similar households, new tax breaks in the reconciliation bill, such as no tax on tips and overtime, would reverse much of this progress.

-

For middle-income groups, the reconciliation bill would eliminate nearly all of the horizontal equity gains achieved by the TCJA, returning tax rate dispersion to pre-TCJA levels.

In addition to extending the expiring provisions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), both the House and Senate versions of the reconciliation bill would add a host of new tax breaks. The Budget Lab has previously analyzed how these proposals would affect what economists call “vertical equity” in the tax code—that is, how they affect the distribution of tax burdens across income levels.

The bill would also impact “horizontal equity”, the notion that taxpayers with similar economic resources should face similar tax burdens. When the tax code includes many preferences for specific types of income or spending, it can result in taxpayers with identical incomes paying different tax rates based solely on the source of their income or their spending patterns. This kind of dispersion in tax burdens within an income group can lead to economically inefficient tax avoidance and foster a sense of unfairness.

While the TCJA generally improved horizontal equity by limiting itemized deductions and consolidating certain tax breaks, the reconciliation bill includes several new tax provisions that create horizontal inequities.1 Most notably, the “no tax on...” provisions create new tax breaks for tipped workers, overtime pay recipients, car loan borrowers, and seniors—making tax liability a function of employment characteristics, borrowing decisions, and age. The bill would also raise the cap on state and local tax (SALT) deductions from TCJA’s level of $10,000 to an income-limited $40,000, increasing the number of taxpayers who itemize and making tax rates more dependent on characteristics like state of residence and homeownership.

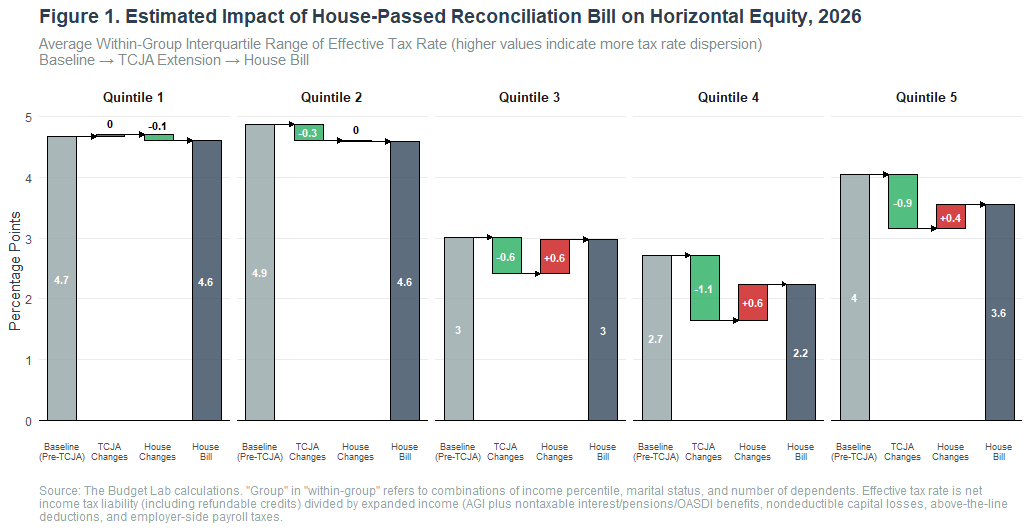

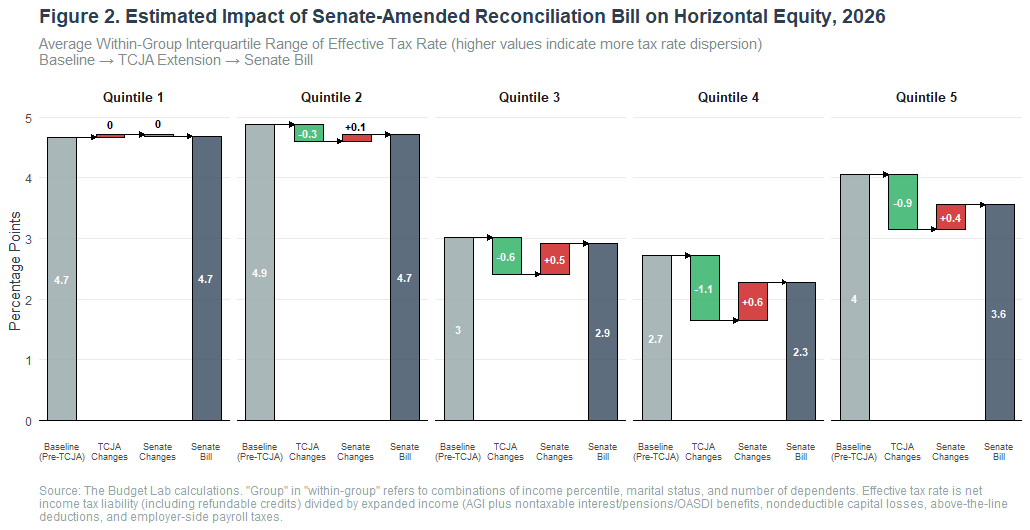

What is the net effect of extending TCJA, which improves horizontal equity, while adding new tax breaks, which worsens it? We use our tax microsimulation model to answer this question, measuring how much tax rates vary after controlling for income and family type. Figures 1 and 2 below show the results.

Extending TCJA would improve horizontal equity. Relative to current law (that is, a TCJA expiration scenario), extending TCJA would meaningfully improve horizontal equity across most of the income distribution. Improvements are most pronounced for the top three quintiles, for whom the TCJA reduced the spread of tax rates among similar filers by roughly 20 to 40 percent on average.

The reconciliation bill would undo almost all of this progress for middle-income taxpayers. The additional tax provisions in each version of the reconciliation bill would undo much of the TCJA’s improvements to horizontal equity. The impact is most stark for the middle quintile, for whom the bill’s new tax deductions, which are targeted to this group, would almost entirely wipe out the TCJA’s horizontal equity gains.

The higher SALT deduction cap leads to more tax rate dispersion for upper-middle- and high-income taxpayers. For the top two quintiles, the higher SALT cap plays a larger role. In the House bill specifically, the expanded Qualified Business Income deduction worsens equity within the top quintile, but the lower Alternative Minimum tax threshold improves it. The net effect of all of these factors is that around half of the TCJA’s progress toward eliminating tax rate dispersion would be undone.

Appendix: Measuring Horizontal Equity

Horizontal equity is challenging to measure in practice. It involves answering several important methodological questions:

Which sources of variance constitute horizontal inequity? The basic goal of a horizontal equity metric is to identify variation in tax burdens that can’t be attributable to differences in income (which is the domain of vertical equity analysis). But it is difficult to define differences in income across tax units with different family sizes. One option is to create an equivalized-scale income measure, but this approach imposes strong assumptions about the “correct” nature of economies of scale within a household.

We take a more flexible approach, treating any tax rate variation due to family type as legitimate differences in economic circumstances. Specifically, we group taxpayers by:

- Income percentile (1-100): This controls for the fact that progressive tax systems intentionally create different tax rates for different income levels.

- Marital status (married/unmarried): This accounts for the different tax treatment of married couples versus single filers.

- Number of dependents (0-3+): This reflects the tax code's adjustments for family size through provisions like the Child Tax Credit and dependency exemptions.

By calculating tax rate dispersion within these groups, we isolate variation that cannot be explained by these fundamental economic and demographic differences. The remaining variation reflects factors like differences in income sources (wages vs. capital gains), spending patterns (mortgage interest, charitable donations), and other tax preferences.

How is tax burden defined? We define tax burden as the effective tax rate (ETR), calculated as net income tax liability (including refundable credits) divided by expanded income. Net income tax liability includes both positive tax liabilities and negative liabilities from refundable credits like the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit. Expanded income is a comprehensive income measure that includes adjusted gross income (AGI) plus above-the-line deductions, nontaxable interest, nontaxable pension and Social Security benefits, nondeductible capital losses, and employer-side payroll taxes. This measure constitutes a denominator for the ETR that is less policy-endogenous than AGI. We drop records with negative income.

How is variance in tax burden measured? We measure tax rate dispersion using the interquartile range (IQR) of effective tax rates within each group. The IQR is the difference between the 75th percentile ETR and the 25th percentile ETR. Importantly, because the units of this measure are percentage points, it retains interpretability when ETRs can be negative. Our results show similar directional patterns when using other range-based metrics or relative measures like standard deviation in tax rates.

The code used to produce the calculations in this report can be found here.

Footnotes

- While the TCJA made many changes that reduce tax rate dispersion within income and family-type groups (e.g. increasing the standard deduction, capping the state and local tax deduction, limiting other itemized deductions, and consolidating child benefits), it also introduced new provisions that increase it (e.g. the deduction for Qualified Business Income). Whether the net effect of these factors is an empirical question, which is answered below in our analysis: the TCJA reduced tax rate dispersion on average.